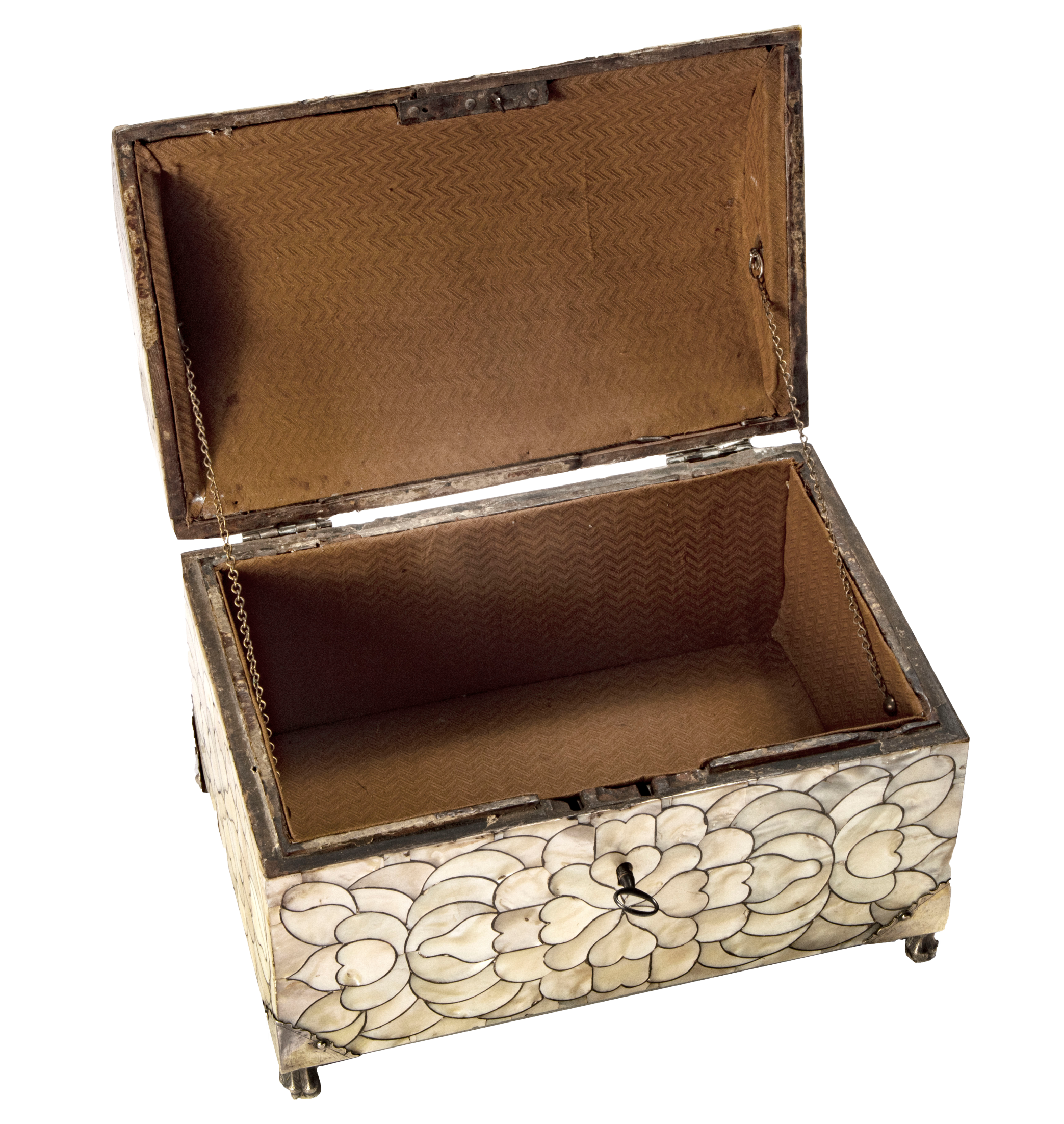

SPANISH COLONIAL, 18th Century

Mother of Pearl Inlaid Wooden Casket

9 ⅞ x 14 ½ x 9 ⅝ inches (25.1 x 36.8 x 24.4 cm)

This mother-of-pearl casket exemplifies the exquisitely crafted decorative objects popular during the 17th and 18th centuries in Colonial Latin America. The decorative technique that creates the striking opalescent finish is known as enconchado. The term derives from concha—the Spanish word for shell—and consists of the application of small pieces of mother-of-pearl, or tesserae, on wooden surfaces, often enhanced by lacquer filament insets between each fragment. The majority of the enconchado decorative objects that survive incorporate this technique in concert with wood and silver inlays, but a few pieces remain that are entirely decorated with mother-of-pearl tesserae; our casket is one such rare example.

Delicately arranged into organic floral motifs, mother-of-pearl pieces cover the entirety of the rectangular trunk and the domed lid of our casket. On each face, a rosette expands into floral forms, and along the curved surface of the lid rows of organic shapes are bookended by borders of contiguous tesserae. The silver mounts of the lid’s hinges are intricately engraved along, and four similarly tooled silver claw feet with corner brackets support the casket.

Decorative objects of this type are not simply valued for their manifest beauty, but also as material representations of the international trade in rare and precious materials between Asia and the New World and the ultimate market for such luxury goods in Spain and Europe. The refined enconchado technique derives from Korean and Japanese lacquer works, but it also references the continued tradition of mother-of-pearl inlay in the Middle East.[i] These visual similarities led to the supposition that this type of object originated in Philippine workshops and, alongside other luxury goods and materials, were imported into the viceregal territories aboard the Manila Galleons. While Peru was receiving substantial quantities of Asian luxury export goods in this period, the profusion in the country of mother-of-pearl decorative objects has led some scholars to speculate that these works may have been produced in local workshops, possibly with the involvement of Asian artisans.[ii]

Two comparable examples of inlaid boxes illuminate the wide geographic range involved in the sourcing of mother of pearl and the creation of these objects. A 17th-century writing box likely made in Peru and possibly involving the work of artists from Manila is remarkably close in technique and appearance (Fig. 1), although the original interior of our casket has been replaced by a cloth liner. Although the demand for this type of exceptional object was concentrated in Lima, there is evidence for the widespread popularity and taste for such items, as well as additional centers of production. A related Sewing or Jewelry Box in the Los Angeles County Museum of Art is thought to have been produced from locally harvested mother-of-pearl and tortoiseshell in Guatemala. Such objects were made for local use, as well as export to Peru, Mexico, or elsewhere (Fig. 2).[iii]

Whether foreign artisans traveled to the Americas, or whether the craftsmen in the Spanish Viceroyalties imitated them is impossible to determine. Regardless of their origin, it is clear that with the burgeoning demand for such items, enconchado works became uniquely colonial art forms, as traditional elements of Asian marquetry were adapted to local aesthetic tastes and combined with imported western forms.

Fig. 1. Mother of Pearl Inlaid Writing Box, Peru, 17th Century, Patricia Phelps de Cisneros Collection.

Fig. 2. Sewing or Jewelry Box, Guatemala, 18th Century, LACMA, Los Angeles.

[i] María Paz Aguiló, “Aproximaciones al estudio del mueble novohispano en España,” En El mueble del siglo XVIII: Nuevas aportaciones a su estudio, Madrid (2008), pp.19-32; and Patricia Díaz Cayeros, “Mobiliario novohispano con diseños geométricos: maderas, carey y hueso,” Res Mobilis, vol. 10, no. 13-2 (2021), pp. 31-35.

[ii] Luis Wuffarden, El Arte de Torre Tagle. La colección del Ministerio de Relaciones Exteriores del Perú, Lima, 2016, pp. 230-231.

[iii] Ilona Katzew and Luis Wuffarden in Archive of the World: Art and Imagination in Spanish America, 1500–1800: Highlights from LACMA’s Collection, ed. Ilona Katzew, exh. cat., Los Angeles, 2022, cat. nos. 67-71, pp. 275-287; Jorge Rivas Pérez, “Transforming Status: The Genesis of the New World Butaca,” in Festivals and Daily Life in the Arts of Colonial Latin America: Papers from the 2012 Mayer Center Symposium at the Denver Art Museum, ed. Donna Pierce, Denver, 2014, pp. 111-128.