SOFONISBA ANGUISSOLA

(Cremona ca. 1532 – 1625 Palermo)

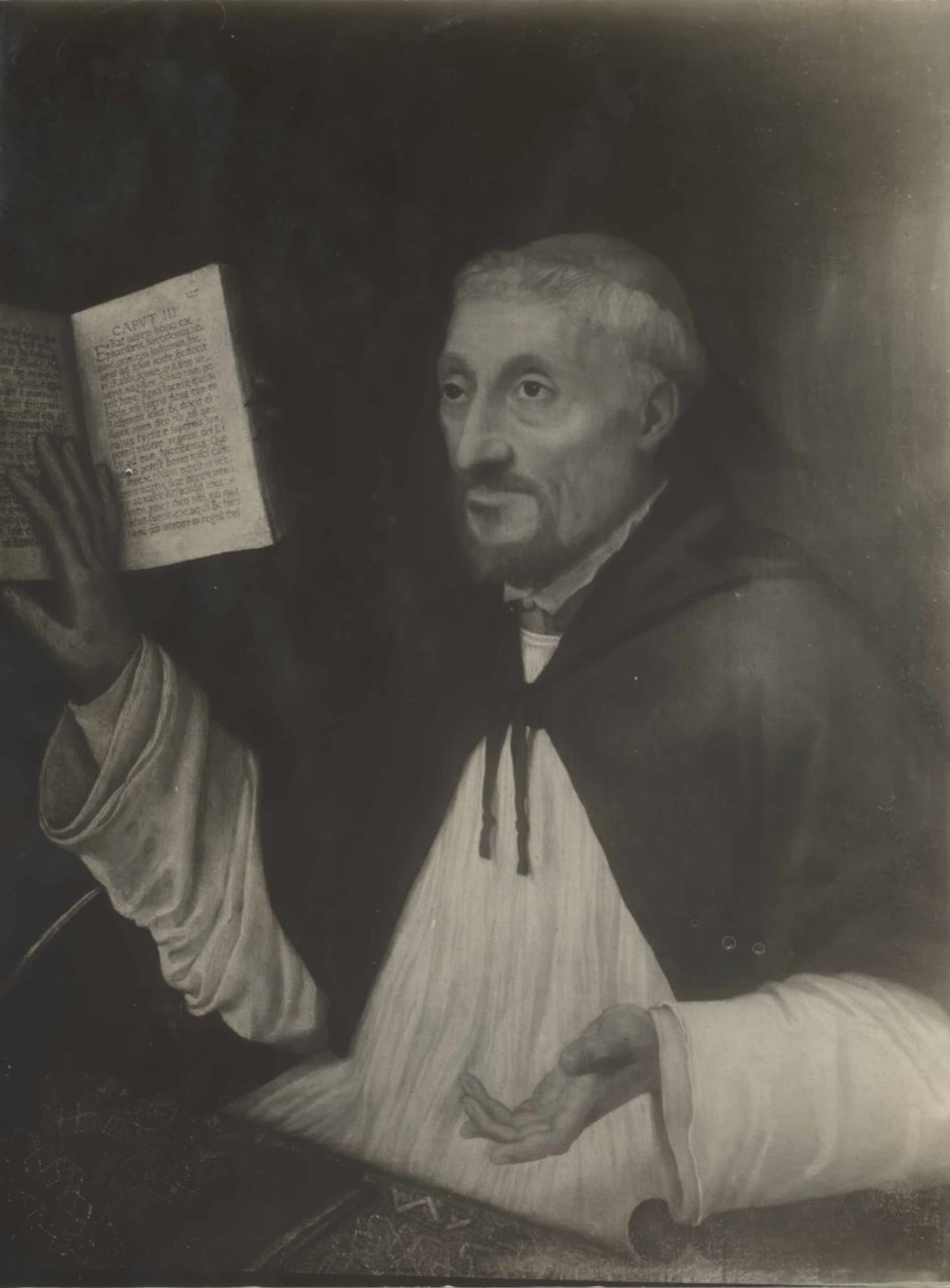

Portrait of a Canon Regular

Signed and dated 1552, lower right:

Sophonisba Anguissola Virgo F/ M D L II

Oil on canvas

35 ½ x 27 ½ inches (90.2 x 69.9 cm)

Provenance:

Augustus Oberwalder [later DeForest], Oberwalder Brothers, New York, 1918.

Anderson Galleries, New York, 28 February 1925, lot 67, as Sofonisba Anguissola, Portrait of St. Seiriol of Anglesey

W.T. Grant’s, New York, 1930

A. S. Faella, New York

Lubin Galleries, New York; where acquired by:

Betty T. Rhew, The Flying Eagle Auction Galleries, Durham, North Carolina; where acquired on 9 January 1977 by:

Dr. Herbert Emanuel Malmqvist and Carita Stahl Malmqvist, Durham, North Carolina; thence by descent to the present owners.

Literature:

Emmanuel Bénézit, Dictionnaire critique et documentaire des peintres, sculpteurs, dessinateurs et graveurs de tous les temps et de tous les pays, vol. 1, Paris, 1976, p. 200.

Ann Sutherland Harris and Linda Nochlin,Women Artists 1550–1950, exh. cat., Los Angeles, 1976, p. 106, footnote 5.

Emmanuel Bénézit, Dictionary of Artists, vol. 1, Paris, 2006, p. 526.

Michael Cole, Sofonisba’s Lesson: A Renaissance Artist and Her Work, Princeton, 2019, pp. 242-243, cat. no. 161, under “Works Documented in Private Collections, Location Undisclosed.”

Michael Cole, “Sofonisba Anguissola and Ippolito Chizzola,” in Viaggio nel Nord Italia: Studi di Cultura Visiva in Onore di Alessandro Nova, eds. D. Donetti, H. Gründler and M. Richter, Florence, 2022, pp. 180-185.

Beatrice Tanzi, “Da Sofonisba al Sojaro: Colombino Raparida nicodemita a campione della Chiesa trionfante,” Ricerche di Storia Dell’Arte, vol. 2 (2024), pp. 41-43, 48, 51-52, figs. 1-2.

Marco Tanzi, Sofonisba Anguissola: Portrait of a Lady in White Satin, Florence, 2024, p. 20.

Michael Cole, “A Rediscovered Painting by Sofonisba Anguissola,” The Burlington Magazine, vol. 167 (June 2025), pp. 572-575.

Beatrice Tanzi, “Letter: Sofonisba Anguissola and the Canons Regular of the Lateran,” Burlington Magazine, vol. 167 (November 2025), p. 1065.

Michael Cole, Sofonisba’s Lesson: A Renaissance Artist and Her Work, 2nd ed., Princeton, forthcoming, pp. xv-xviii, 176, cat. no. 22, under “Documented Works/Works with Uncontested Signatures.”

Sofonisba Anguissola is recognized as the greatest female portraitist of the Italian Renaissance. Unlike her near contemporaries who were the daughters of painters and trained by their fathers, Sofonisba hailed from a noble family in Cremona and was trained with her sister Elena by the local painters Bernardino Campi and Bernardino Gatti. She was the eldest of seven children, and it appears that each of her five sisters received some training in the arts, the younger ones likely taught by Sofonisba herself. Not only was Sofonisba by far the most accomplished of her siblings, but she is also the first female artist in the history of Italian art to achieve international acclaim. At a young age she was known to both Michelangelo and Giorgio Vasari, who each played a role in fostering and promoting her talent. In 1559 she was called to Madrid, where she served as attendant to the Infanta Isabella and as lady-in-waiting to Elisabeth of Valois, the Queen of Philip II. Her new position provided stature and security, but severely limited the creativity shown in her brilliant portraits of the 1550s, as she was now required to follow the stylistic formulae of the Spanish court. Sofonisba continued to pursue her art in Spain and later in Palermo and Genoa, where she settled following her marriage. However, it is Sofonisba’s early work in Italy—particularly her portraiture—that best reveal her gifts as a painter of great sensitivity and originality.

Our canvas is one of fewer than twenty signed paintings by the artist.[1] It is prominently signed in the lower right in Sofonisba’s characteristic hand—she signs as “virgo” and gives the date of 1552 in Roman numerals, making it one of Sofonisba’s earliest securely dated works. Until recently, this painting had been known only through a black-and-white photograph (with an annotation recording the signature) taken roughly 100 years ago during the sale of the painting in New York (Fig. 1).[2] This photograph, first signaled by Dr. Ann Sutherland Harris in a footnote of her landmark 1976 exhibition catalogue, was considered anew and served as the basis for the inclusion of the painting in Dr. Michael Cole’s 2019 monograph on Sofonisba. Since the publication of Cole’s monograph, the painting has happily resurfaced in a North Carolina private collection.

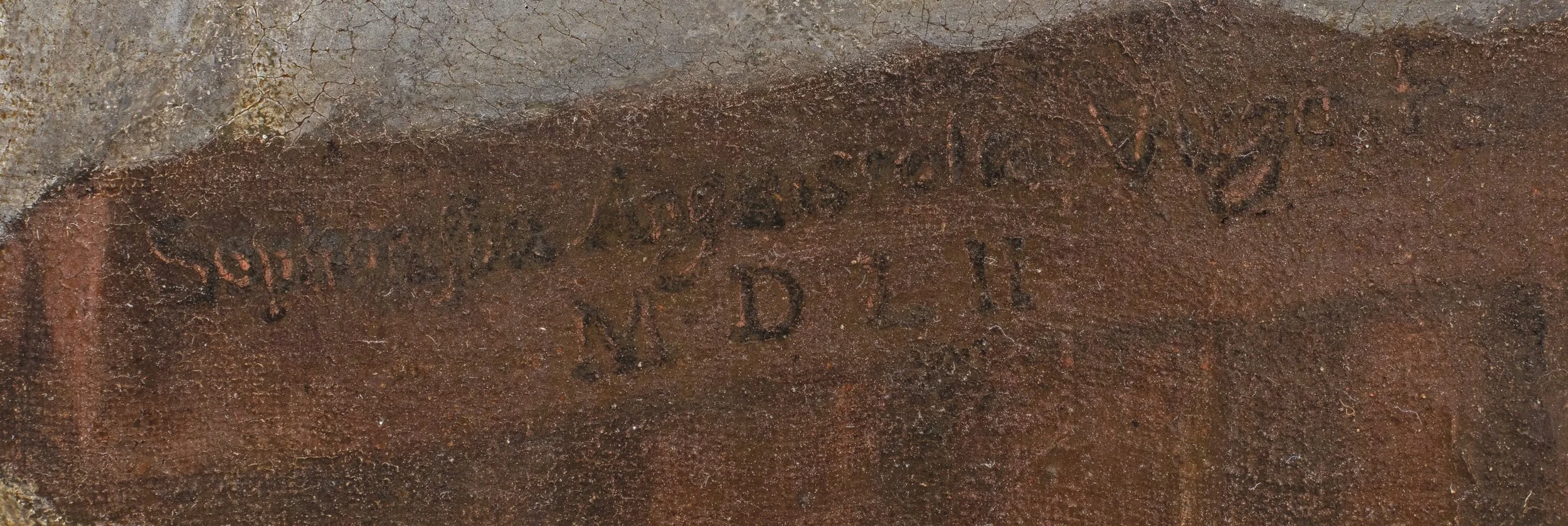

Sofonisba’s signature on this work has been made more legible by the recent conservation of the portrait (Fig. 2). Painted illusionistically in black letters with brown highlights as if carved into the arm of the chair, the signature can now be properly read as “Sophonisba Anguissola Virgo F/ M D L II” (rather than “Sophonisba Angussola,” as it had been previously transcribed).[3] As Cole has written of the work, the 1552 date “puts the painting among Sofonisba’s early Cremonese works, the group in which it also fits pictorially and conceptually.”[4]

Fig. 1. Sofonisba Anguissola, Portrait of a Canon Regular, photograph of ca. 1928 from the Photoarchive of the Frick Art Research Library, New York.

Fig. 2. Detail of signature in the present work.

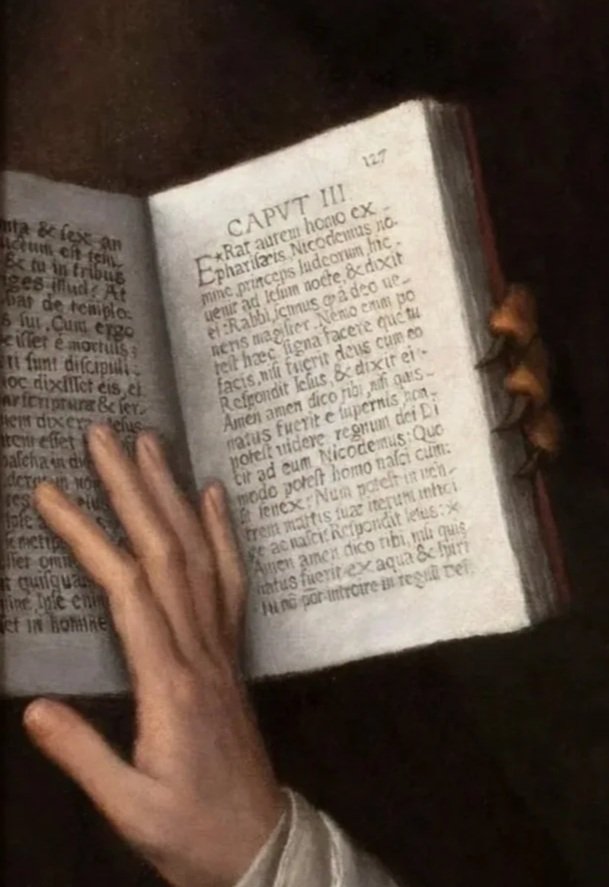

Sofonisba rendered this compelling portrait with her characteristic directness in the presentation of the subject. The sitter is closely cropped and placed close to the pictorial frame, prompting an intimate encounter with the viewer. Sofonisba’s ability to infuse her portraits with psychological insight—a defining feature of her art—is here on full display. Remarkably and ambitiously, Sofonisba has introduced a narrative element into the portrait, depicting the sitter in the act of lecturing, his left hand gesturing while with his right hand he reaches out to touch the open tome. The text is written in a prominent, legible script meant to be read by the viewer—similar to the passages found in the open book of her Self-Portrait in the Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna (Fig. 3) and the horoscope being written by the Dominican astrologer in a portrait that is today known only through photographs (Fig. 4). As in the Portrait of a Dominican Astrologer, which is of a later moment, our portrait shows the sitter actively engaging in an activity and with the viewer, thereby transforming the subject from a static portrait into an enlivened scene. This became a successful formula for Sofonisba that she employed in many works of her early Cremonese period.

Fig. 3. Sofonisba Anguissola, Self-Portrait, ca. 1554, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna.

Fig. 4. Sofonisba Anguissola, Portrait of a Dominican Astrologer, 1556, oil on canvas, formerly Calligaris Collection, current whereabouts unknown.

The sitter sits at a desk that is covered with a Turkish carpet (Fig. 5)—a preferred device of the artist that is found in several variations in her works.[5] Dr. Walter B. Denny has commented on Sofonisba’s distinctive shorthand in rendering the texture of a knotted-pile carpet. He writes: “The carpet here is clearly a small-patterned Holbein (Fig. 6), but the pattern has been distorted, and there is a very curious design/pattern improvisation in the lower left corner.”[6] He further notes that quasi-improvisation is not unusual in the history of early modern European painters depicting rugs. Denny also raises the possibility that the rug that Sofonisba used as her model may have been subject to repairs and re-knotting, and that it could have already been an antique at the time of its representation in the painting—possibly explaining its asymmetrical pattern.

Fig. 5. Detail of the rug in the present work.

Fig. 6. Small-pattern Holbein rug, Palazzo Lomellino, Genoa.

While the identity of the sitter in our portrait is unknown, he can be confidently identified as a Canon Regular of the Lateran. The Canons Regular were an order of preachers closely related to but distinct from the Dominicans. They followed the rule of Saint Augustine and had a significant presence in Cremona centered around the monastery of San Pietro al Po. Sofonisba painted other portraits of anonymous members of the order at the start of her career, including her portrait in the Pinacoteca Tosio-Martinengo in Brescia (Fig. 7) and another portrait sold at Dorotheum in Vienna in 2013 (Fig. 8).[7] Each of these sitters can be identified as Canons Regular based on their distinctive garb. Their habits consist of a white cassock with a white linen rochet, along with a black cloak that is open at the front and includes an attached black hood.

Fig. 7. Sofonisba Anguissola, Portrait of a Canon Regular of the Lateran, oil on canvas, Pinacoteca Tosio Martinengo, Brescia.

Fig. 8. Sofonisba Anguissola, Portrait of a Canon Regular of the Lateran, oil on canvas, Dorotheum, Vienna, 2013.

Our painting is not only the earliest of the portraits of Canons Regular—the Pinacoteca Tosio-Martinengo portrait is dated 1556 and the Dorotheum portrait shows a similar maturity of style—but it is also among Sofonisba’s earliest works. The only other dated paintings from her early twenties are the Portrait of a Nun (Elena Anguissola) of 1551 in Southampton (Fig. 9) and that of ca. 1554 in the Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna (Fig. 3).[8] Our painting is one of Sofonisba’s most ambitious early works, and possibly also among her first private commissions and portraits to depict someone outside of her family.

Fig. 9. Sofonisba Anguissola, Portrait of a Nun, ca. 1551, Southampton City Art Gallery, UK.

Dr. Beatrice Tanzi has proposed to identify the subject of our portrait as Colombino Rapari, a Cremonese Canon Regular who had an illustrious ecclesiastical career and a long connection with the monastery of San Pietro al Po, including as abbot.[9] This proposal, which rests largely on visual comparison with the depiction of Rapari as a donor figure in a painting of 1557 by Bernardo Gatti, has been rejected by Cole.[10] While there is some resemblance between the two men depicted in each canvas, it is hard to accept that in the span of five years, the figure depicted in the present work could have developed a significant widow’s peak that interrupted his tonsure and that he became significantly more wrinkled (Figs. 10-11).

Fig. 10. Detail of the sitter in the present work.

Fig. 11. Detail of Bernardo Gatti, Adoration of the Shepherds, 1557, San Pietro al Po, Cremona.

Uncertainty about the identity of our sitter, as well as those of the other anonymous Canons Regular painted by Sofonisba, are likely to persist. However, the rich details of the portrait may eventually provide further clues. The prominence of the legible text in the upper left invites the viewer’s attention (Fig. 12). Each page contains biblical passages in Latin from the Book of John—the lefthand page quotes John 2:20-25 (fragmentarily) and the righthand page John 3:1–5.[11] An eagle, the traditional symbol of Saint John, grasps the book with his talons, hovering somewhat menacingly in the dark. Because of the clear references to John the Evangelist it might be tempting to propose that the sitter shares the Apostle’s name, Giovanni. While this merits further investigation among the registers of the Canons Regular of San Pietro al Po, it is more likely that the selected passage gives context to the sitter’s occupation as a member of the order.

The protagonist of John 3:1-5 is Nicodemus, the Pharisee who secretly visited Jesus in the night to receive his teachings. The story of Nicodemus became a touchstone for religious conflict in the 16th century, as reformers frequently referred to it when discussing those who concealed their acceptance of Martin Luther’s teachings. The episode to which the painting refers became emblematic following John Calvin’s 1544 publication L’Excuse à Messieurs les Nicodémites. Both Calvin’s followers and detractors came to consider Nicodemus as the exemplum for those who abided by Catholic doctrine and rituals while inwardly accepting Calvin’s creed. As Cole has outlined, early reform movements had sprung up in the region around Cremona, and Canons Regular were regularly engaged to preach against the ideas disseminated by the Reformation.[12] In the present portrait, the sitter’s speaking gestures and engagement with the viewer can be read as the figure giving a discourse on the text—presumably arguing against the reformers who strayed from Catholic orthodoxy. Given his depiction in his role as a preacher, the subject likely had an elevated position and status within the monastery of San Pietro al Po in Cremona.

Fig. 12. Detail of the text in the present work.

[1] As grouped under “Documented Works/ Works with Uncontested Signatures” in Michael Cole, Sofonisba’s Lesson: A Renaissance Artist and Her Work, Princeton, 2019, pp. 12, 156-167.

[2] Ann Sutherland Harris signaled the existence of a photograph in the Frick Art Reference Library, New York, that documented this painting, the whereabouts of which was then unknown. A note in the file of the Photoarchive indicates that the photograph was obtained from G. Frank Muller in 1928. See: https://library.

frick.org/permalink/01NYA_INST/d73c5u/alma991012301189707141.

[3] Sofonisba similarly signed on the arm of the chair in her Portrait of an Old Man (Burghley House, Lincolnshire, UK).

[4] Cole, “A Rediscovered Painting by Sofonisba Anguissola,” p. 574.

[5] Turkish carpets appear also in Sofonisba’s Portrait of the Artist’s Sisters Playing Chess (ca. 1555, National Museum, Poznań) and Portrait of an Old Man (Burghley House, Lincolnshire, UK). Dr. Walter B. Denny has noted that the same rug is depicted in both works—a small so-called 2-1-2 large-patterned Holbein—suggesting that this is a re-used studio prop.

[6] We are grateful to Dr. Denny for sharing his observations on the present portrait (written communication, 27 December 2025).

[7] https://www.dorotheum.com/cz/l/4218608/.

[8] Cole has noted that the dating of Portrait of a Nun in Southampton—long thought to be Sofonisba’s earliest surviving painting—may need rethinking. The date of 1551 is based on reports of a fragmentary inscription containing the Roman numerals ‘MXDLI,’ which has not been seen for more than a century. Given the unknown condition of the inscription at the time it was read, it is worth considering the possibility that the dates included further digits at the end—perhaps it could have read MDLII, MDLIV, or MDLIX. See: (Forthcoming) Michael Cole, Sofonisba’s Lesson: A Renaissance Artist and Her Work, 2nd ed., Princeton, 2026, p. xv.

[9] Beatrice Tanzi, “Da Sofonisba al Sojaro: Colombino Raparida nicodemita a campione della Chiesa trionfante,” Ricerche di Storia Dell’Arte, vol. 2 (2024), pp. 41-55.

[10] Cole, “A Rediscovered Painting by Sofonisba Anguissola,” pp. 572-575; and (Forthcoming) Cole, Sofonisba’s Lesson, 2nd ed., pp. xvii-xviii.

[11] John 2:20-25 from the King James Bible: “20 Then said the Jews, Forty and six years was this temple in building, and wilt thou rear it up in three days? 21 But he spake of the temple of his body. 22 When therefore he was risen from the dead, his disciples remembered that he had said this unto them; and they believed the scripture, and the word which Jesus had said. 23 Now when he was in Jerusalem at the passover, in the feast day, many believed in his name, when they saw the miracles which he did. 24 But Jesus did not commit himself unto them, because he knew all men, 25 And needed not that any should testify of man: for he knew what was in man.” John 3:1-5 from the King James Bible: “1 There was a man of the Pharisees, named Nicodemus, a ruler of the Jews: 2 The same came to Jesus by night, and said unto him, Rabbi, we know that thou art a teacher come from God: for no man can do these miracles that thou doest, except God be with him. 3 Jesus answered and said unto him, Verily, verily, I say unto thee, Except a man be born again, he cannot see the kingdom of God. 4 Nicodemus saith unto him, How can a man be born when he is old? can he enter the second time into his mother's womb, and be born? 5 Jesus answered, Verily, verily, I say unto thee, Except a man be born of water and of the Spirit, he cannot enter into the kingdom of God.”

[12] For further details on the context of the reform movement in Italy in this period, particularly in the Cremonese context, see: Cole, “A Rediscovered Painting by Sofonisba Anguissola,” pp. 574-575; and (Forthcoming) Cole, Sofonisba’s Lesson, 2nd ed., pp. xv-xviii.