GIOVANNI BATTISTA BEINASCHI

(Fossano, near Turin 1636-1688 Naples)

The Martyrdom of Saint Peter

Oil on canvas

114½ x 76 inches

(290.8 x 193.1 cm)

Provenance:

with Simoni del Cava, until 1817; where acquired by:

Johann I Josef, Prince of Liechtenstein, Duke of Troppau and Jägerndorf (1760–1836); thence by descent in the Liechtenstein Garden Palace, Rossau, Vienna to:

Aloys II, Prince of Liechtenstein (1796–1858), Liechtenstein Garden Palace, Rossau, Vienna; by descent to:

Johann II, Prince of Liechtenstein (1840–1929), Liechtenstein Garden Palace, Rossau, Vienna; by descent to:

Franz Joseph II, Prince of Liechtenstein (1906–1989), Liechtenstein Garden Palace, Rossau, Vienna, until transferred to Schloss Eisgrub, Lednice, Bohemia, from November 1942 until October 1944, when moved to

Schloss Moosham, Unternberg, Lungau, until February 1945, when moved to Schloss Vaduz, Liechtenstein; by descent to:

Hans-Adam II, Prince of Liechtenstein, Schloss Vaduz, Liechtenstein until 2008; by whom sold at Christie’s, London, July 9, 2008, lot 127, as Giovanni Battista Beinaschi; where acquired by:

Private Collection, London, 2008–2013

Literature:

Liechtenstein Ankaufsverzeichnis (manuscript acquisitions list), no. 99.

Katalog der Fürstlich Liechtensteinischen Bilder-Galerie im Gartenpalais der Rossau zu Wien, Vienna, 1873, p. 45, no. 371, as Jusepe de Ribera.

Jakob von Falke, Katalog der fürstlich Liechtensteinischen Bilder-Galerie im Gartenpalais der Rossau zu Wien, Vienna, 1885, p. 7, no. 41, as Jusepe de Ribera.

August L. Mayer, Jusepe de Ribera (Lo Spagnoletto), Leipzig, 1908, p. 195, as by a student or imitator of Jusepe de Ribera (listed under “Schulbilder, Nachahmungen”).

Adolf Kronfeld, Führer durch die Fürstlich Liechtensteinsche Gemäldegalerie in Wien, 2nd edition, Vienna, 1929, p. 13, no. 41; 3rd edition, Vienna, 1931, p. 16, no. 41, as Jusepe de Ribera.

Juan Antonio Gaya Nuño, La pintura española fuera de España: historia y catálogo, Madrid, 1958, p. 279, no. 2312, as by Jusepe de Ribera.

Craig McFadyen Felton, “Jusepe de Ribera; A Catalogue Raisonne,” unpublished PhD dissertation, University of Pittsburgh, 1971, p. 619, cat. no. X519, as an unaccepted attribution to Jusepe de Ribera.

Francesco Petrucci, “Beinaschi tra Roma e Napoli,” in Giovanni Battista Beinaschi: pittore barocco tra Roma e Napoli, ed. Vincenzo Pacelli and Francesco Petrucci, Rome, 2011, pp. 51–52, fig. 65, as Giovanni Battista Beinaschi.

Antonio Gesino, in Giovanni Battista Beinaschi: pittore barocco tra Roma e Napoli, ed. Vincenzo Pacelli and Francesco Petrucci, Rome, 2011, pp. 271–272, cat. no. B1, illustrated, as Giovanni Battista Beinaschi.

This monumental altarpiece is the single-most important painting by Giovanni Battista Beinaschi to have left Italy. A dramatic work Caravaggesque in its lighting, theatricality, and affect, it was long considered to be by Jusepe de Ribera, whose name remains emblazoned on the picture frame in which the painting has been exhibited since its tenure in the collection of the princes of Liechtenstein.

Beinaschi was born near Turin, and his earliest training was with Esprit Grandjean, an artist active at the Savoy court. By 1652 he had moved to Rome, where he was to live for more than a decade before the lure of ecclesiastical patronage brought him to Naples. Although he is often referred to as piemontese, Beinaschi perfected a style that shows little evidence of his Piedmont origins. Rather, it seems most indebted to the work of Giovanni Lanfranco, whose works Beinaschi knew well (he had engraved Lanfranco’s altarpieces in San Andrea della Valle and San Carlo Catinari), although he apparently never met the elder artist, who died in Rome only a few years before Beinaschi arrived there. Beinaschi moved to Naples around 1664, where he painted both altarpieces and fresco cycles in churches throughout the city. His work was consistently in demand for his entire career and he received a succession of commissions both private and public (although predominantly ecclesiastic) with the result that nearly all of his paintings remain in Italy, most in the places for which they were painted.

Fig. 1. Photograph of Room III in the Liechtenstein Garden Palace, Rossau, Vienna, ca. 1900. The Beinaschi Martyrdom of Saint Peter can be seen to the right of Guido Reni’s Adoration of the Shepherds, now in the National Gallery, London.

The Martyrdom of Saint Peter is one of Beinaschi’s most impressive works, yet due to its inaccessibility, it has until recently remained relatively unknown and unrecognized as a significant work by the artist. From 1817 until 2008 it was in the collection of the Princes of Liechtenstein, exhibited before World War II in the Liechtenstein Palace in Vienna (Fig. 1), but then consigned successively to family castles in Bohemia, the Austrian Alps, and Liechtenstein. Over all these years it was considered to be by Jusepe de Ribera, but as early as 1908 August Mayer had questioned that attribution. It was not until a century later that Nicola Spinosa definitively recognized Beinaschi’s authorship. His opinion was subsequently confirmed by Francesco Petrucci and Antonio Gesino in the recent catalogue raisonn. of the artist’s work and made yet more apparent following recent conservation of the painting, which removed generations of dirt and discolored varnish. All of these scholars place the painting relatively early in the painter’s maturity, for Spinosa around 1660, for Petrucci and Gesino slightly later, ca. 1663–1665. This would suggest that the original site for the altarpiece was either in Naples, executed at the beginning of Beinaschi’s tenure there, or in Rome, among the last works painted before his departure.

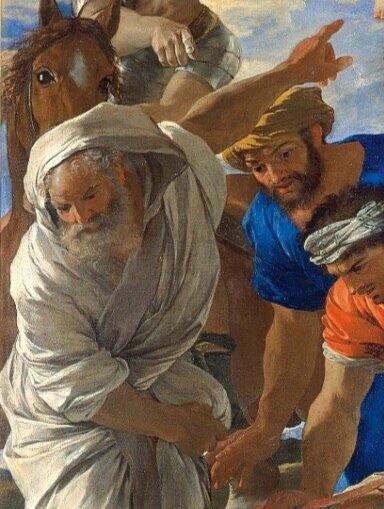

The composition is a swirling depiction of the martyrdom of Saint Peter, legendarily crucified upside down. Peter has been nailed to the cross by his feet alone, as his arms flail wildly. In emphatically portraying Peter’s unbound arms, Beinaschi seems to be referring to Christ’s prediction of the form of Peter’s death in John 21:18–19: “But when thou shalt be old, thou shalt stretch forth thy hands, and another shall gird thee and lead thee whither thou wouldst not. And this he said, signifying by what death he should glorify God.” Four soldiers are occupied with raising the cross. One at the lower right steadies the top against the ground. Above him, another pulls down with both hands and all his weight on the rope that leads through an unseen pulley to lift the bottom of Peter’s cross. Two other soldiers at the left, one behind the other, struggle to raise it upright. At the upper center an angel descends, gazing directly at Peter and gesturing towards heaven with one hand as he delicately bestows a martyr’s palm with the other, his wings and robes obscuring the spectral glow of the moon.

A pagan priest at the center of the painting grasps Peter’s right wrist and points with his left arm to the seated statue at the upper right, demanding his submission to the Roman deity. With uncommon historical accuracy Beinaschi has modeled the idol on the monumental Jupiter Verospi, a third-century replica of the original by Apollonius, which was the principal cult figure in the Temple of Jupiter Capitolinus in Rome at the time of Peter’s martyrdom (Figs. 2-3). In the seventeenth century the sculpture was on view in the courtyard of the Palazzo Verospi in Rome and was later acquired for the Vatican by Pope Clement XIV in 1771.

Fig. 2. Detail of the sculpture in the upper right of the present work.

Fig. 3. Engraving of Jupiter [Iuppiter Verospi] in Jean Barbault, Recueil des divers monumens anciens, Roma, 1770, pl. 64.

Beinaschi’s altarpiece has been described as a “magisterial translation of a Caravaggesque subject treated by many of the greatest exponents of baroque and classicizing painting.”[i] Indeed, it seems to echo Guido Reni’s altarpiece, now in the Pinacoteca Vaticana, as well as Caravaggio’s in Santa Maria del Popolo, while explicitly quoting the figure of the priest in Nicolas Poussin’s Martyrdom of Saint Erasmus, painted for Saint Peter’s (Figs. 4-5).[ii] Analogies with the works of Mattia Preti (such as his Martyrdom of Saint Peter at the Barber Institute, Birmingham) and Luca Giordano suggest a Neapolitan origin,[iii] and thus a slightly later date for the altarpiece, but until documentation emerges, the specific origin of this powerful Baroque canvas is likely to remain unknown. Beinaschi treated the subject in two other canvases, both considerably smaller and later in date: one is on deposit from the Brera in the church of Santa Maria Assunta in Golasecca, Varese; the other is in the collection of Marcello Aldega in Rome.[iv]

Fig. 4. Detail of the pagan priest in the present work.

Fig. 5. Detail of Nicolas Poussin’s Martyrdom of Saint Erasmus, Saint Peter’s, Vatican City.

[i] Antonio Gesino, in Giovanni Battista Beinaschi: pittore barocco tra Roma e Napoli, ed. Vincenzo Pacelli and Francesco Petrucci, Rome, 2011, pp. 271–272, cat. no. B1.

[ii] Francesco Petrucci, “Beinaschi tra Roma e Napoli,” in Giovanni Battista Beinaschi: pittore barocco tra Roma e Napoli, ed. Vincenzo Pacelli and Francesco Petrucci, Rome, 2011, pp. 50–51, figs. 66 and 67.

[iii] Petrucci, “Beinaschi tra Roma e Napoli,” pp. 51–52, fig. 68.

[iv] Giuseppe Porzio, in Giovanni Battista Beinaschi: pittore barocco tra Roma e Napoli, ed. Vincenzo Pacelli and Francesco Petrucci, Rome, 2011, pp. 51–53, fig. 69 and pp. 278–279, cat. no. B12 for the Brera version; and pp. 52–53, fig. 70, and p. 279, cat. no. B13 for the Aldega version.