WILLIAM BEWICK

(Harworth 1795 – 1866 Darlington)

After Michelangelo Buonarroti

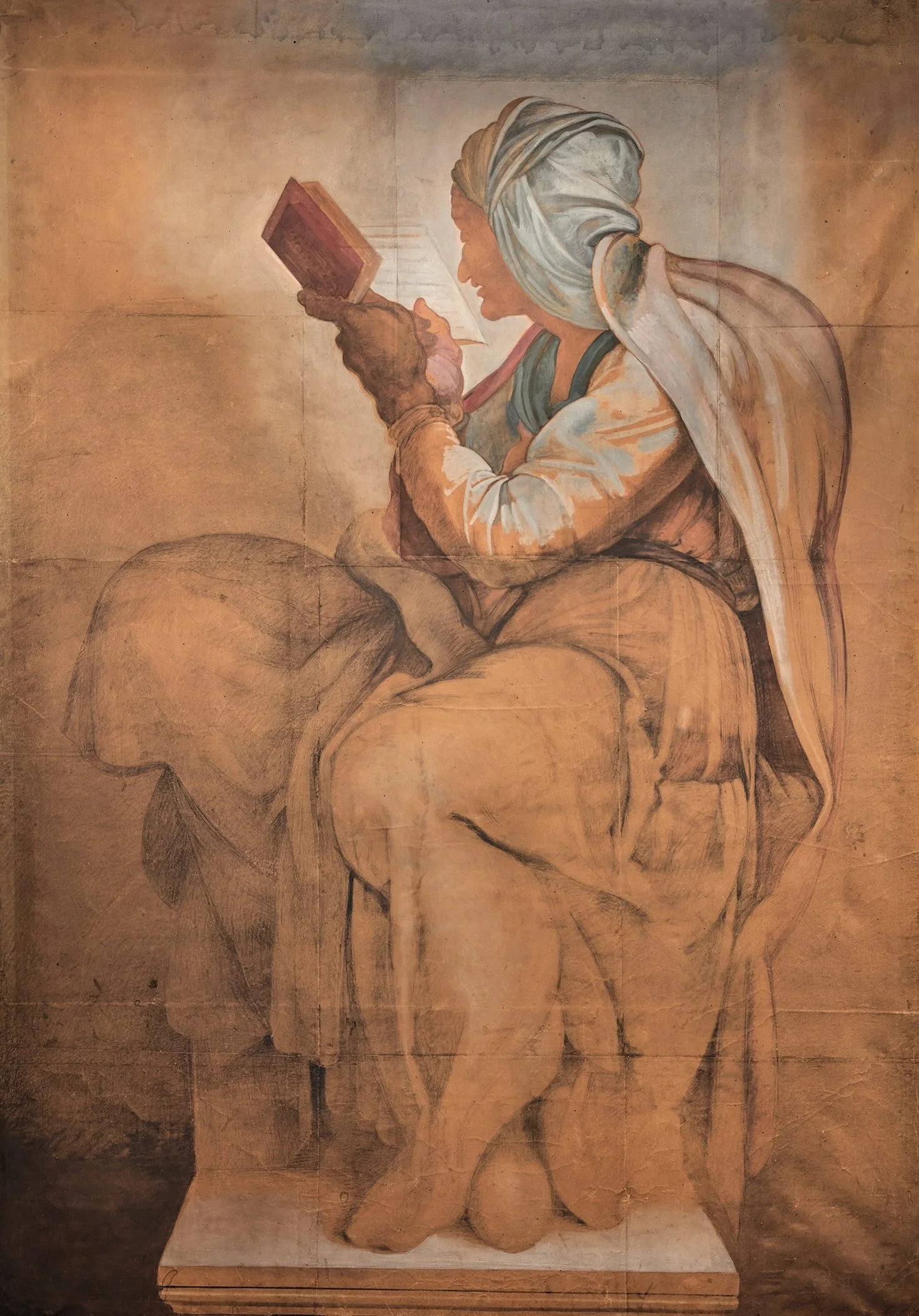

The Persian Sibyl

Mixed media on multiple sheets of paper, laid down on canvas

116 x 83 inches (295 x 211 cm)

Provenance:

(Possibly) Sir Thomas Lawrence, London, until 1830; his estate sale:

Christie’s, 18 June 1831, lot 143;[1] bought by Hutchinson.

Private Collection, Scottsdale, Arizona.

Private Collection, Phoenix, Arizona, until 2025.

Michelangelo’s frescoes in the Sistine Chapel are perhaps the most famous and iconic paintings of the Italian Renaissance. From the time of their completion in 1512 until the present day they have attracted the attention, admiration, and awe of visitors worldwide. But until the development of photography, they could be studied only through small drawn or printed copies of dramatically reduced size. Without one’s visiting the Chapel personally, it was impossible to acquire a sense of the scale and power of Michelangelo’s masterpiece.

The present work is a survivor of a remarkable and mostly forgotten chapter in the study and veneration of Michelangelo’s work. It is a life-size drawn and painted copy of one of the mighty figures from the ceiling, the Persian Sibyl, made by a British artist working in the 1820s on a scaffold sixty feet above the floor of the Sistine Chapel. Combining tracings from the fresco, chalk drawings, and brushwork with paint media, the artist, William Bewick, sought to reproduce not only the design of the figure in actual size, but, as significantly, the effect the work had on the viewer.

William Bewick had come to London from Darlington in County Durham to study under the artist Benjamin Robert Haydon. Part of his training involved copying works of art, a practice at which Bewick excelled. His life-sized drawings of the Elgin Marbles, which were first exhibited at the British Museum in 1817, were acquired by Goethe. They remain in his house museum in Weimar (Fig. 1).[2]

Fig. 1. William Bewick, Theseus from the Elgin Marbles, Goethe National Museum, Weimar.

The genesis of the Sistine Chapel project is well documented. In his biography of Bewick, Thomas Landseer writes:

“Sir Thomas Lawrence, President of the Royal Academy, had conceived the idea of illustrating his Presidency by presenting to the School of the Royal Academy a series of full-sized copies in oil, of Michael Angelo’s Prophets and Sibyls in the Sistine Chapel at Rome; and hearing of Mr. Bewick's great skill as a copyist, and of his earnest desire to visit Italy, he offered him one hundred guineas for a large copy of the Delphic Sibyl in the Sistine Chapel.”[3]

The undertaking was expanded from the outset. As related in a letter of 29 June 1826, Bewick met with Lawrence and received the commission to make a series of full-sized copies of Sibyls and Prophets from the Sistine ceiling, receiving a stipend for the project. He left for Italy on 2 July, arriving in Genoa after a lengthy journey by sea, then proceeded down the peninsula to Rome where he commenced work in October 1826, writing home:

“I have had an interview with the major-domo of the Pope, and have succeeded in getting permission to study in the Sistine Chapel, from those stupendous works of Michael Angelo. You may judge of the scale of the objects when I tell you that the canvas I have ordered for one figure of a Prophet is eleven feet high, and this only takes in one figure from the top of the head to the feet, and the prophet is sitting. It is my most anxious wish to obtain copies of all the best of Michael Angelo’s works that are in this chapel, as they are decidedly superior to anything of epic composition in existence; and indeed they are so tremendous in power and grandeur, that no one has hitherto attempted so arduous an undertaking. I must erect a scaffolding from forty to fifty feet high to enable me to finish them.”[4]

Bewick then wrote to Sir Thomas Lawrence:

“You were kind enough to request me to write to you from Rome, so soon as I should have seen the Sistine Chapel, and put in progress the copies you did me the honour to commission me to make from those stupendous works of Michael Angelo. You likewise spoke of a select set of copies of these glorious things, which had long been the object of your solicitude, as you wished to propose them to the Royal Academy. The idea of getting large copies of the Prophets, Sibyls, and some others, seems to excite expectations of pleasure in the breasts of every one; and the thought of the Royal Academy of London possessing such copies would be much for the interest of the British school, and on a task of such a nature I should enter with all the enthusiasm that the magnificence of the subject would inspire. The expense of such a set of copies would be comparatively trifling to an institution like that of the Royal Academy. At any rate, in the projection of a new building, it might be of importance to bear them in mind.”[5]

Bewick soon wrote of commencing a six-foot high Delphic Sibyl and an eleven-foot Prophet Jeremiah. The sporadic letters that survive from his tenure in Rome reveal the challenges of the project as he could work in the Sistine Chapel only when it was not being used for ecclesiastical purposes. The investiture of cardinals, various papal ceremonies, Holy Week—all necessitated Bewick’s having to take down his scaffolding and erect it again afterwards. Further delays were caused by the Pope’s aversion to the smell of paint (requiring the opening of chapel windows and an extra five-day buffer on either side of his appearances), the heat of the summer, Bewick’s own illnesses, and finally, the death of Pope Leo XII in 1829 and the ensuing conclave that sealed the Chapel for more than a month. Bewick returned to England the following year.

We do not know how many large pictures and preparatory drawings Bewick made during his time in Rome. In 1828 Bewick sent two full-sized pictures to Lawrence and, not entirely surprisingly, they proved to be too large to hang in his home. At his death in 1830, Lawrence had five in his possession and, as the Royal Academy declined to acquire them, they were sold at Lawrence’s estate auction at Christie’s on 18 June 1831. They were each catalogued as by Bewick “from the picture by Michael Angelo in the Sistine Chapel, the size of the original.” The subjects were the Delphic and Libyan Sibyls, the Prophets Jeremiah and Daniel, and what was described as a “Sitting Figure.” This might be identifiable with the present work.

On Bewick’s return to London, he took premises in Mayfair and had at least one exhibition of his Sistine Chapel works. An article in the March 1840 Art-Union extolled Bewick’s drawings and advocated for their acquisition by the Royal Academy:

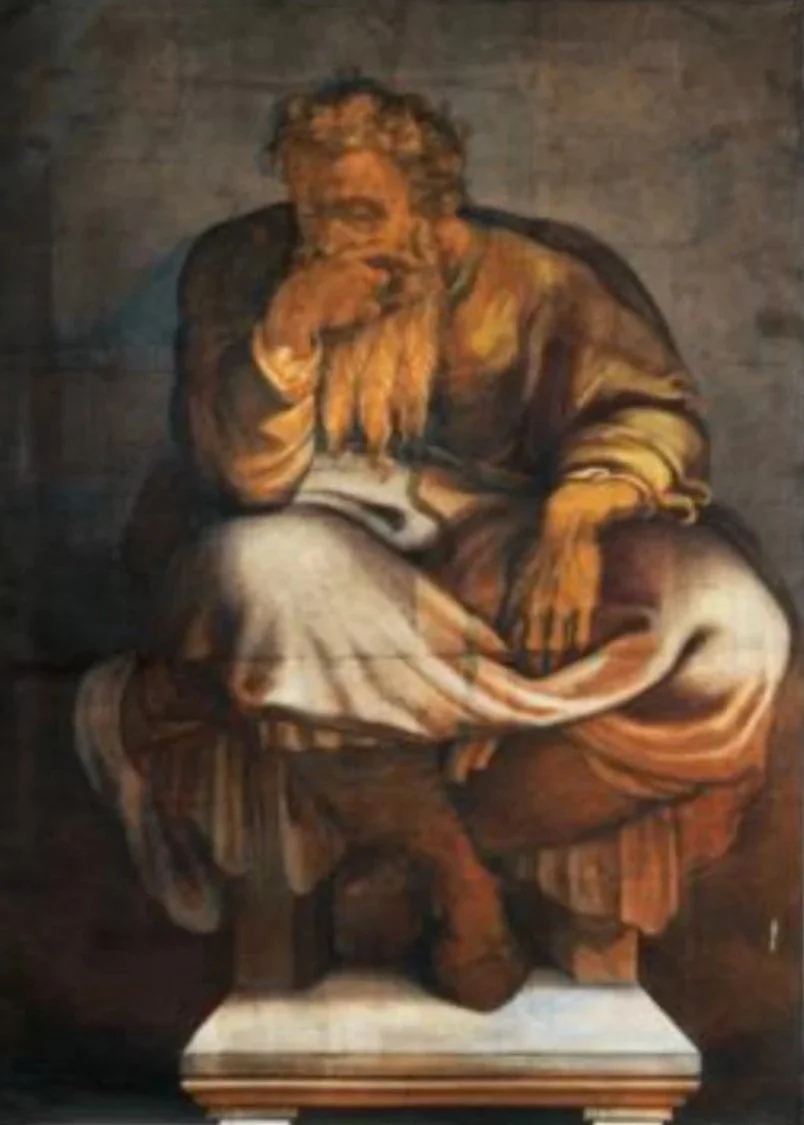

“Among the copies are the five Sibyls Delphica, Cumaa, Persica, Lybica, and Erythræa. The first is the most wonderful-a combination of beauty with power in the countenance, such as no other painter has ever executed, or, perhaps, ever conceived. The aged Persica pores over a book. Lybica is rising and closing a volume. Of the Prophets, Isaiah is listening to a sacred messenger; Jeremiah is mourning over the fearful nature of his own prophecies; Joel is perusing a scroll; Ezekiel, Zachariah, and Daniel, are the others. But any attempt to describe them would be absurd.”[6]

A subsequent article describes his exhibiting the drawings by gas-light and that “it is more than probably the Royal Academy will be the owners of this valuable collection; no difficulty having arisen on the ground of ‘price,’ the only obstacle being ‘want of room.’[7] But this enthusiasm was not shared by Bewick’s old teacher Benjamin Haydon, who wrote critically in his diary of the pictures and disparagingly of the artist:

“Saw Bewick (my Pupil’s) copy of the Sibyls & prophets of Michel-Angelo very finely drawn-as copies, but it is wonderful how little a Man who copies well can do for himself. The style of Michel Angelo belongs to the place he painted in, and was necessary to render his designs visible or effective. This seen in rooms seems exaggeration. In the naked he was not as deep as the Greeks, and all my assertions are confirmed. But the Erethrean & Lybica are very fine in expression…. I had not seen my old Pupil for 17 years! His mind seemed quite gone…. I could not help glorying that I had not left my native land! He had copied, worshipped, studied, dwelt so long on Michel Angelo, he seemed abroad on any thing else! I was astonished. This comes of such submissive adoration.”[8]

Most of the exhibited drawings were studies or reduced-size cartoons after the chapel figures, but Bewick clearly replicated his full-sized pictures on more than one occasion. Two examples of his Prophet Jeremiah are known—one in the art collection of his home-town library in Darlington (Fig. 2), and the other formerly on the art market in Vienna (Fig. 3).[9] It is possible that one of these was that once owned by Sir Thomas Lawrence. And a set of the Prophets and Sibyls was purchased from the estate of Bewick’s widow by Dean William Charles Lake for Durham Cathedral. One of these, that of the Libyan Sibyl, was sold from the Cathedral in 1978 (Fig. 4).[10] The location of the others, once in the Cathedral Dormitory, is not known. Two signed and dated paintings of prophets after Michelangelo, appeared on the London art market in 1976. That of Joel was signed and dated “Rome, July 22, 1827”; the other, Ezekiel, exactly a month later.[11]

Fig. 2. William Bewick, Prophet Jeremiah, Darlington Library, 235 x 145 cm.

Fig. 3. Bewick, Prophet Jeremiah, formerly art market, Vienna, 288 x 208.5 cm.

Fig 4. William Bewick, Libyan Sibyl, formerly Durham Cathedral, later art market, London.

No other version of our Persian Sibyl is known, but whether ours was the “Sitting Figure” owned by Sir Thomas Lawrence or a different effort by Bewick cannot be determined. Michelangelo had placed the monumental figure of the sibyl on a stone throne as she peered intently at her book of prophesies. As a legendarily aged figure, she is enveloped in robes for warmth and due to her failing vision holds the book close to her eyes. Bewick has eliminated the architectural setting and the attendant figures present in Michelangelo’s fresco to focus on the sibyl herself (Figs. 5-6). His aim is less in the faithful reproduction of the colors—which of course have changed dramatically since Bewick’s time—than the rendering of the shape and forms of the figure. Still, there are subtle variations in the scale and position of the figure between the original and Bewick’s version. In the present work, the sibyl’s head is less inclined and the size and position of her proper right leg have been adjusted. Similar differences can be detected in Bewick’s other copies. These are almost certainly due to the fact that Michelangelo’s figures are painted on the vaulted ceiling of the Chapel. When Bewick assembled his drawings of the frescoes, he necessarily transposed tracings made from the curved surface to the flat plane of the canvas. Whatever the differences, it is astounding to be confronted by Michelangelo’s figure in its true size—permitting both an appreciation of the power of the image, and the tremendous effort of the artist who labored to create it.

Fig. 5. Michelangelo, Persian Sibyl, Sistine Chapel, Vatican City.

Fig. 6. The present work.

[1] One of five pictures by William Bewick after the frescoes in the Sistine Chapel. The cataloguing for lot 143 is as follows: “Ditto [Bewick], A Sitting Figure from Ditto [from the picture by Michael Angelo in the Sistine Chapel, the size of the original].”

[2] Frederick Cummings, “B. R. Haydon and His School,” Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes, vol. 26, no. 3/4 (1963), p. 372. Another copy by Bewick was bought by Sir William Hamilton.

[3] Thomas Landseer, Life And Letters of William Bewick (Artist), London, 1871, vol. 1, pp. 273-274. Interestingly, an earlier suggestion to paint life-size copies of the Sistine Chapel figures was made by the poet Ugo Foscolo during an at times heated conversation between him, William Wordsworth, and Bewick at Benjamin Haydon’s residence (op. cit., p. 87). Lawrence was acutely aware of the limitations of reproductions after Michelangelo’s frescoes, having visited the Sistine Chapel in 1819 and having relied on Adamo Scultori’s engravings of the ceiling, a copy of which he owned for his own study. See Scultori’s engraving of the Persian Sibyl:

Adamo Scultori, Persian Sibyl, from his series of 72 engravings after Michelangelo,

ca. 1547–1587, British Museum, London.

[4] Landseer, Life And Letters of William Bewick, vol. 2, p. 26

[5] Landseer, Life And Letters of William Bewick, vol. 2, pp. 27f.

[6] “The Works of Michael Angelo in the Sistine Chapel, Rome,” The Art-Union, vol. 2, March 1840, p. 40. See: Landseer, Life And Letters of William Bewick, vol. 2, p. 130. Two

[7] “Chit Chat; Mr. Bewick’s Copies from Michael Angelo,” The Art-Union, vol. 1, June 1840, p. 98.

[8] Willard Bissell Pope, The Diary of Benjamin Robert Haydon, Cambridge, vol. 4, 196, pp. 633f. Haydon’s comments on Bewick are filled with antagonism and bitterness, not only due to his defensiveness from his never having visited Italy, but also as Bewick had not assisted Haydon financially when Haydon fell into debt and was imprisoned in 1827.

[9] Darlington Borough Art Collections, 235 x 145 cm. (http://www.artuk.org/artworks/jeremiah-43984). Dorotheum, Vienna, 10 November 2022, lot 151, 288 x 208.5 cm, as Follower of Michelangelo. See Bendor Grosvenor: “Was a Vienna auction’s €6,000 ‘copy’ of the Sistine Chapel’s ceiling actually by Michelangelo?,” The Art Newspaper, 21 December 2022 (https://www.theartnewspaper.com/2022/12/

21/was-a-vienna-auctions-6000-copy-of-the-sistine-chapels-ceiling-actually-by-michelangelo).

[10] 117 ½ x 84 ¼ inches (297.8 x 214 cm). See: Hubert David Hughes, A History of Durham Cathedral Library, Durham, 1925, p. 94. Christie’s, London, 2 June 1978, lot 214; subsequently Christie’s South Kensington, 19 October 2000, lot 316; later in the collection of Tony Ryan at his Georgian manor house, Lyons Demesne, in County Kildare, Ireland; his estate sale, Christie’s, 14 July 2011, lot 69. From the photographs it appears as if the work had been damaged by having been folded in the past.

[11] Christie’s, London, 2 June 1976, lots 219 and 221, both catalogued as bodycolour on brown paper, laid on canvas, 118 x 84 ¾ inches.