BARTOLOMÉ ESTEBAN MURILLO

(Seville, 1618 – 1682)

Young Christ (Niño Jesús)

Oil on canvas embellished with rock crystal and gilded decorations

37 ⅜ x 23 ½ inches (95 x 59.8 cm)

Provenance:

Private Collection, Spain.

This compelling and richly decorated painting of the Young Christ is a new addition to the oeuvre of Bartolomé Esteban Murillo, one of the premier Spanish painters of the 17th century. Murillo spent most of his life in his native Seville and undertook many important public and private commissions as the leading painter in his city. He is perhaps best known for his graceful religious works and tender depictions of children—two aspects of his artistic output that are on full display in the present painting. Our Young Christ is completely unique among the surviving works by Murillo as a painting embellished with rock crystals and gilded ornamentation set into the canvas support, likely executed in collaboration with a specialized goldsmith. The tradition of embedding precious stones into religious paintings can be traced back to 13th century Italy but was employed only for special commissions in the centuries following. The exceptional quality of this painting paired with the masterfully applied precious materials makes the rediscovery of this work by Murillo particularly significant.

The Christ Child is depicted close to the pictorial surface and is set against a stark, black background that helps to push the figure forward in space. While Murillo has imbued Christ with a realism characteristic of his paintings of children, the child is a representation of a static devotional figure. The work follows a common compositional format in Spanish art of translating sculpted devotional images into paint and presenting them as if set on an altar. While sculpted depictions of the Infant Christ Blessing—often imported from Flanders—had long been popular in Spain, there was a significant increase in domestic production of such sculptures in the 17th century in connection to widespread devotion to the cult of the Christ Child, particularly among confraternities and female cloistered orders. Confraternities had a custom of utilizing so-called imágenes de vestir—sculptures specifically designed to be clothed with lavish garments—most commonly employed in depictions of the Virgin Mary and the adult Christ carrying the cross. Local devotion in Seville and Andalusia to the Young Christ and the existence of a sculpted imagen de vestir of this subject in the period is evinced by a painting of similar composition by an anonymous Sevillian artist (Fig. 1). Rather than following a prescribed prototype, as was so often the case with paintings of devotional sculptures, Murillo here presents the Young Christ in his distinctive and personal style, creating a work that is at once painted sculpture and sculpted painting.

Fig. 1. Sevillian School, 17th Century, Young Christ, oil on canvas, Hospital del Pozo Santo, Seville.

Christ stands on a decorative plinth with his head gently inclined and his eyes peering downward as if looking at a devotee praying at the altar. With his right hand, he appears to bless the viewer before him, while in his left he holds a finely decorated cross, the edges of which are slightly elevated from the surface of the canvas. Murillo has rendered the child’s hands, facial expression, and youthful locks of hair with great sensitivity and with a sense of movement that enlivens the figure. Christ’s blessing gesture can be compared with the left hand of his counterpart in Murillo’s altarpiece of Saint Anthony of Padua painted for the convent of the Capuchins in Seville (Fig. 2). The format of the painting and the compositional device of Christ engaging with a devotee suggests that our painting was intended for either for a domestic setting or a small ecclesiastical space devoted to personal and private devotion. The painting may have been commissioned from Murillo by a patron who was a member of a confraternity that had a particular veneration to such a sculpted image. Sculpted depictions of the young Christ in this period were generally patterned on standardized iconographic types that present the child in various poses and with different attributes. Our painting does not correspond exactly to any one of these well-known types, but Christ’s blessing gesture, cross, sandals, pink tunic, and green bow are tied to several of these iconographies, among them the Christ Child in Triumph, the Niño Jesus de Belen, and the Infant of Prague. Dr. Ronda Kasl has suggested that Murillo likely based our Christ Child on the famed Niño del Sagrario by Juan Martínez Montañes in the Seville Cathedral (Fig. 3). This sculpture was widely known in Seville and venerated due to its prestigious location, and it is considered the prototype for sculpted depictions of the Christ Child in Seville. Interestingly, the contract for the commission of the Niño del Sagrario from Montañes stipulates that the Christ Child should have a rough-hewn cross made of ebony (today replaced by a chalice and host), possibly simulated here in the faux bois treatment of the painted cross.i

Fig. 2. Bartolomé Esteban Murillo, Detail of Saint Anthony of Padua with the Young Christ, oil on canvas, Museum of Fine Arts, Seville.

Fig. 3. Juan Martínez Montañes, Christ Child (Niño del Sagrario), 1606–1607, polychromed wood, 31 ½ inches tall, Church of El Sagrario, Seville Cathedral.

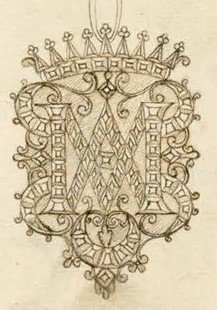

The strong visual impact of this painting is due in large part to the abundance of rock crystal and gilded decorations that adorn Christ’s garments, his cross, and the halo composed of alternating rays and flames. The use of rock crystal in jewelry and decorative objects came into fashion in Europe in the second half of the 16th century. The geometric settings of the crystals and the gilded S-shaped motifs are closely linked to the works of Spanish goldsmiths and jewelers of the period, and the design and application of these elements would have been undertaken by a highly skilled practitioner of this field. The simulation of embroidery and lacework—particularly in the neckline, the hem, and the cuffs of the sleeves—is especially refined and reflects the rich and costly nature of the fabrics that adorned imágenes de vestir. The fact that the intricate decorative elements are raised from the surface of the painting also mimics the appearance of the garments used on sculpted devotional images. These were often embroidered with gold thread that was filled so that they stood in relief, as well as decorated with motifs executed with gold sheets known as oro llano.ii The prominent jewel tied with a white bow in the center of Christ’s chest is also notable. Known as a zifra del nombre de la Virgen—as it contains the intertwined initials A and M referring to the Virgin Mary (“Ave Maria”)—these jewels became popular in the second half of the 17th century (Fig. 4). The crown above the initials, a typical feature of zifras, is here decorated with red, pink, and green pastes, simulating rubies and emeralds. A contemporary goldsmith’s drawing of a zifra, as well as a surviving example of the period, reveal the craftsman’s adeptness at replicating the object of reference on the painted surface (Figs. 5-6).iii

Fig. 4 Detail of the zifra in the present work.

Fig. 5 Drawing of a zifra, ca. 1630.

Fig. 6. 17th-century zifra, Museum of San Francisco, Valladolid.

The elaborate applied decorations on the surface of the canvas clearly relate to embellished Spanish Colonial paintings of the early 17th century. Perhaps the most well-known work of this type is the Virgin of Guadalupe painted by the Spanish Hieronymite monk Diego de Ocaña (1565–1608), who travelled across South America between 1599 and 1605 as a special emissary of his order tasked with spreading the cult of the Virgin of Guadalupe. Ocaña painted several images of the Virgin, the most famous and venerated being that in Bolivia’s Cathedral of Sucre (Fig. 7). While some works of this type acquired additional embellishments from devotees over the centuries, it is clear that Ocaña’s painting was conceived with the idea of affixing precious materials to its surface. He relates in the account of his travels (Relación del viaje de fray Diego de Ocaña por el Nuevo Mundo, 1599–1605) the process of his production of the image, first painting on canvas and afterwards affixing pearls, gems, and other stones that had been collected by the head of his brotherhood from the women of the Spanish upper class in Bolivia.ivAnother embellished painting by a Spanish artist working in the New World is the Virgin of the Rosary by Alonso de Narvaez (active ca. 1550–1583) in Chiquinquirá, Colombia which displays raised gilt decorations (Fig. 8). While most embellished Spanish Colonial paintings are images of the Virgin and Child,v one example of an embellished Young Christ, thought to be 17th-century Bolivian, is in the collection of the Hermandad de Montserrat, Seville (Fig. 9). Another, most likely by an anonymous artist of the Seville school, is roughly contemporary with the present work but manifestly of lesser quality (Fig. 10). Seen as a group, these paintings reflect a fluidity in the transmission of both imagery and materiality between Spain and the New World—of which Seville, the major Spanish port to the Americas, was the natural conduit.

Dr. Luis Eduardo Wuffarden has written that the custom and taste for painted imágenes de vestir adorned with applied precious stones and materials originated in the New World and reflected the opulence of the American continent. He suggests that embellished works of this kind were likely brought back to Spain by so-called “indianos” —newly enriched returning Spaniards eager to flaunt their economic power. The existence of this work by Murillo raises important questions about the connections between Viceregal painting and the reciprocal exchanges with the artistic traditions of Seville.vi

Fig. 7. Diego de Ocaña, Virgin of Guadalupe, ca. 1601, oil on canvas embellished with precious stones, Cathedral of Sucre, Bolivia.

Fig. 8 Alonso de Narvaez, Virgin of the Rosary (Our Lady of Chiquinquirá), oil on canvas embellished with raised gilt decorations, Chiquinquirá, Colombia.

Fig. 9. Bolivian, Potosi School, 17th Century, Young Christ, oil on canvas embellished with stones and gilded decorations, Hermandad de Montserrat, Seville.

Fig. 10. Seville School, 17th Century, Young Christ, oil on canvas embellished with stones and gilded decorations, City Hall, Seville.

Recent x-ray imaging of the painting has revealed several details about its production (Fig. 11). The presence of the dazzling opaque white of the ornamentation indicates that a principal reason for the remarkable survival of the raised decoration was that the pastiglia into which the rock crystal decorations have been inset was composed of a gesso containing substantial amounts of durable and resilient lead white. By comparison, the few replacements to be found in the ornamentation are formed of a less robust material, which appears fainter in the image. Furthermore, examination of the painting under a microscope has confirmed that the paint layer of the garments is contemporaneous with the pastiglia decorations. The paint can be observed on top of the edges of the raised decorations, suggesting that the three-dimensional elements were applied before the final paint layer was added.vii Also noted was the consistent use of gold leaf and the presence of a consistent craquelure pattern commensurate with the contemporary creation of the entire work.

Fig. 11. X-Ray of the present work.

Dr. Enrique Valdivieso González has confirmed Murillo’s authorship based on firsthand inspection and has described the painting as “exceptional, unique, and extraordinary” (written communication, 16 September 2021).”viii He dates the painting to 1670 to 1675—the height of Murillo’s career and the period in which he painted most of his depictions of children. Valdivieso has written the following of this work: “The painting exhibits an intense quality typical of Murillo’s mature period and presents physical features that only he could capture with such delicate beauty, particularly in the head, hands, and feet of the child. Christ’s face especially stands out, as he peers down with half-closed eyes contemplating the devotee that would be positioned at his feet…The child’s facial expression is framed by a radiant circular halo, the undulating rays reinforcing the spiritual intensity of the image.”

[i]Verbal communication. For a discussion of Juan Martínez Montañes’ Niño del Sagrario, see: Ronda Kasl, “Delightful Adornments and Pious Recreation: Living with Images in the Seventeenth Century,” in Sacred Spain: Art and Belief in the Spanish World, ed. Ronda Kasl, Indianapolis, 2009, pp. 160-162.

[ii] Susan Verdi Webster, Art and Ritual in Golden-Age Spain: Seveillian Confraternities and the Processional Sculpture of Holy Week, Princeton, 1998, p. 113.

[iii] A report by Dr. Carolina Naya Franco, professor of Gemology and Art History at the University of Zaragoza and a specialist in goldwork and the history of fashion, is available upon request.

[iv] Astrid Windus, “‘Y yo, con buen celo y animo, tome los pinceles del oleo...: dynamics of cultural entanglement and transculturation in Diego de Ocana’s Virgin of Guadalupe (Bolivia, 17th–18th centuries),” Colonial Latin American Review, vol. 27, no. 4 (2018), pp. 437-438.

[v] Other known examples include a 18th-century Peruvian triptych with some later embellishments known as the Virgen de Mayo today in the Carmelite Convent of the Assumption in Cuenca, Ecuador (Suzanne Stratton-Pruitt, The Art of Painting in Colonial Quito, Philadelphia, 2012, pp. 227-229, cat. no. 60); and the Virgin of Immaculate Conception at the New Orleans Museum of Art (https://noma.org/collection/our-lady-of-the-immaculate-conception/), which has colored rock crystals set into the ring and earring.

[vi] A catalogue entry on this painting by Dr. Wuffarden is available upon request. “Es bastante probable que el gusto por tales aplicaciones fuera llevado por los así llamados “indianos”, es decir aquellos españoles que volvían a la peninsula enriquecidos y deseosos de hacer ostentación de su poder económico. De hecho, fue en el Nuevo Mundo donde arraigó con fuerza la costumbre de “aderezar” las imágenes pintadas con aplicaciones de oro, plata, perlas y piedras preciosas que reflejara la opulencia del continente americano. […] Todo indica que ambas piezas comparten no solo una fuente gráfica común, sino el peculiar tratamiento de pedrería sobre la túnica del Niño Jesús, lo que plantea sugestivas interrogantes sobre las conexiones entre la pintura virreinal y los probables intercambios de ida y vuelta con tradiciones artísticas andaluzas.”

[vii] We are grateful to Dianne Modestini and Molly Hughes-Hallett of The Conservation Center of the Institute of Fine Arts, NYU for their observations and assistance in examining and imaging this work.

[viii] A catalogue entry on our portrait authored by Dr. Valdivieso is available upon request.