RANDOLPH ROGERS

(Waterloo, NY 1825 – 1892 Rome)

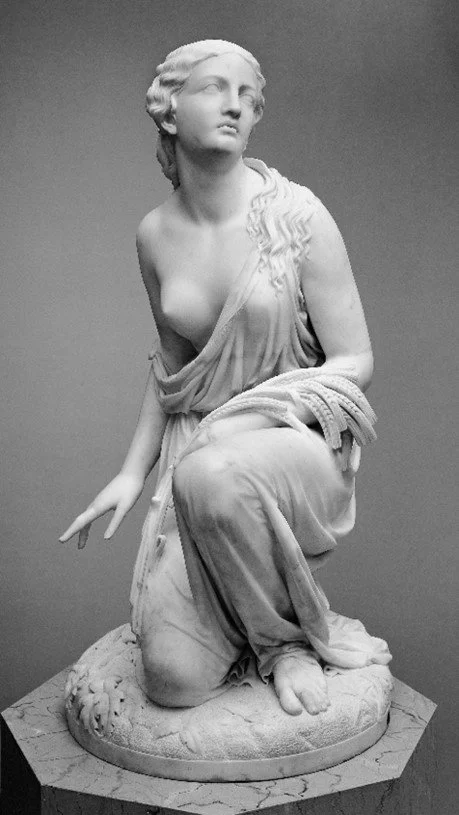

Night

Signed and dated on the reverse: Randolph Rogers Sc / Florence 1850

Marble

24 x 18 inches (60.9 x 45.7 cm)

31 x 20 x 10 inches (78.7 x 50.8 x 25.4) with socle

Provenance:

Ogden Haggerty, New York, 1851.

Ronald Vollbrecht, Guilderland, NY, ca. 1995–2025.

Exhibited:

National Academy of Design, 1852, no. 267, as “A Bust—Night.”

Literature:

National Academy of Design Exhibition Record, 1826–1860, vol. 2, New York, 1943, p. 101, cat. no. 267.

Millard F. Rogers, Jr., Randolph Rogers: American Sculptor in Rome, Amherst, 1971, pp. 15, 154, cat. no. 4.

Randolph Rogers was born in upstate New York and spent most of his youth in Ann Arbor, Michigan, before moving to New York City around 1847. His first efforts in sculpture began at that time while working at a dry goods store, and in 1848 his employers, impressed by his evident talent, subsidized his travel to Italy. There he became a student of the famed Neo-classical sculptor Lorenzo Bartolini at the Accademia di Belle Arti in Florence. Rogers mastered modeling in clay and plaster, employing, as Bartolini did, Italian carvers to translate his sculpture into finished marble works. Bartolini died in 1850 and the following year Rogers left for Rome, where he was to remain for the rest of his life. Although he regularly received significant commissions from American collectors and institutions throughout his career, he lived and worked in a succession of studios in Rome, where he became the first American to be elected an academician at the Accademia di San Luca.

Night is the earliest surviving sculpture by Rogers, having recently been discovered in a New York collection. It is signed and dated “Florence 1850” and was sent to New York for the artist’s first public exhibition at the National Academy of Design in 1851. There it was listed as owned by Ogden Haggerty (1810–1875), a New York commercial auctioneer and noted arts patron.[1] The bust was commended in the press, if briefly: “a finely executed piece of sculpture” (New York Daily Herald) and a “beautiful marble bust of ‘Night’” (Home Journal). More descriptive praise came from The Evening Post: “Another head, in marble, called “Night,” the first work of a young American artist, Randolph Rogers, now in Italy, is full of promise. The lids are visibly heavy with sleep, and every feature, every muscle, has the appearance of being surrendered to the drowsy influences of the hour.”[2]

Bartolini’s influence can be seen in the contrasts of vigorous passages of vibrant carving—such as the richly detailed hair and folded drapery—with the quiet, idealized forms of the face and nude body. But where the expressions of Bartolini’s subjects tended toward the abstract and distant in pure Neo-classical tradition, Rogers, even in this first work, has introduced an element of subtle emotion to his subject. Night is wistful in expression, her embodiment of the end of the day enhanced by the gentle tilt of her head, suggesting the onset of slumber. As the anonymous writer of the Evening Post perceived, Rogers has endeavored to imbue every element of the white marble sculpture with suggestions of the coming evening. What at first glance seems to be a crescent moon—

the traditional symbol of the goddess Diana—in fact forms a more intricate allegorical tiara. Behind the moon is a low relief of the setting sun, while on either side a row of stars appears.[3] Resting atop the tiara is the beginning of the draped fabric that covers the head, falls down her back (partially revealing long locks of hair), and then wraps around her arms and torso while gracefully exposing her breasts to the viewer. Night was an extremely ambitious undertaking for the twenty-five-year-old sculptor.

Rogers followed Night with the work that would bring him acclaim and success, Ruth Gleaning (Fig. 1). Begun in Florence in 1850 and completed in Rome the following year, it was to prove tremendously popular among American collectors with over thirty examples known to have been carved in marble. While a larger-scale work, and one in which the element of narrative has been introduced, it shares strong stylistic parallels with Night in the handling of elements of detail, ornament, and expression, as well as its treatment of nudity.

Night is a unique work—no other example of it is known, and it is one of the few works for which the artist’s original plaster model was not included among the collection the artist donated to the University of Michigan.[4] Nor is any photograph of it recorded. In addition to being an exceptionally beautiful work of art, its recovery adds additional perspective to our knowledge of the career of this remarkable sculptor.

Fig. 1. Randolph Rogers, Ruth Gleaning, 1850–1851; carved 1855–1856, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

[1] Haggerty (1810–1875) was a successful dry goods auctioneer in New York under the name “Haggerty & Co.” He was one of the founders of the Century Association and both a collector and patron of the arts, particularly noted for his support of George Inness. His daughter Anna married Robert Gould Shaw, the celebrated colonel of the Massachusetts 54th Regiment, whose valor and sacrifice are commemorated by Augustus St. Gaudens’s bronze monument.

[2] New York Daily Herald, 21 April 1851, p. 3; “Fine Arts; National Academy of Design,” The Home Journal, 15 May 1852, p. 2; “The Exhibition of the Academy,” The Evening Post, 16 April 1852, p. 2.

[3] Interestingly, a similar treatment of the tiara—with stars and a crescent moon, but without the setting sun—was employed by Hiram Powers in his 1853 bust Diana (examples at the High Museum of Art, Atlanta; Chrysler Museum, Norfolk; Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, DC; and National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC).

[4] Millard F. Rogers, Jr., Randolph Rogers: American Sculptor in Rome, Amherst, 1971, p. 154f. The sad fate of the cast collection is recounted by Millard Rogers. Of the 94 plaster casts (plus casts for Rogers’s doors to the Capitol Building in Washington) given to the University of Michigan, only three survive today in the collection of the University Art Museum. The rest had been destroyed intentionally or by neglect.