THOMAS WORTHINGTON WHITTREDGE

(American, 1820 – 1910)

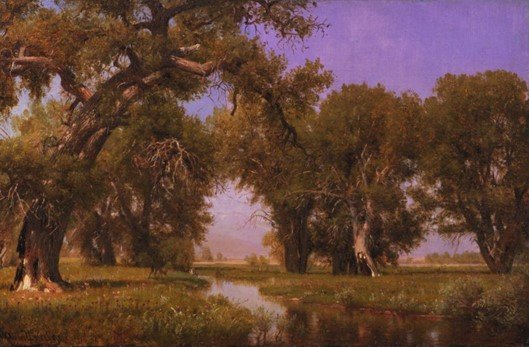

Indian Encampment Under Trees (On the Cache La Poudre River, Colorado)

Signed, lower left: W Whittredge

Oil on board

18 ⅞ x 27 ½ inches (48 x 70 cm)

Provenance:

(Possibly) I. A. Rose, New York, early 20th century

Marion Morgan Kemp (1860–1963), by 1910 (according to an inscription on the reverse)

Private Collection, Germany, until 2019

Worthington Whittredge and Albert Bierstadt were the preeminent nineteenth-century painters of the American West. But where Bierstadt’s grand canvases portrayed the splendor of mountains, torrents, and sweeping vistas, set within turbulent clouds and dramatic light effects, Whittredge’s vision was one of broad and placid plains, depicting a quiet landscape in which man coexisted peacefully with nature. If Bierstadt strove for the sublime, Whittredge chose the majestic.

Over a period of eleven years Whittredge painted about forty paintings and oil sketches of Western subjects. Four were gallery-sized canvases: three roughly 40 x 60 inches—Crossing the Platte River (The White House, Washington, D.C.), Crossing the Ford (The Century Association, New York), and On the Cache La Poudre River (Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, TX)—with one somewhat smaller, On the Plains (St. Johnsbury Athenaeum, St. Johnsbury, VT). [i] The balance are more modestly sized—generally between 8 and 14 inches in height. Our view of the Colorado plains at twilight is a newly discovered painting by Whittredge, notable both for its larger scale and as it is set at one of the artist’s most beloved sites, a place along the Cache La Poudre River, just east of the town of Greeley, about fifty miles northeast of Denver. While much has changed over 150 years, a recent photograph taken close to where Whittredge painted shows a remarkably similar view (Fig. 1).[ii] This scene was clearly a favorite of the artist and his patrons, as he produced several variants from this vantage point—each different in size and staffage—over the course of the most successful decade of his career.[iii] The present work is likely the earliest version and stands out for the vibrancy of color, the expert translation of evening light into paint, and its depiction of a procession of Native Americans returning to an encampment nestled among the trees.

Fig. 1. View of the Cache La Poudre River at twilight

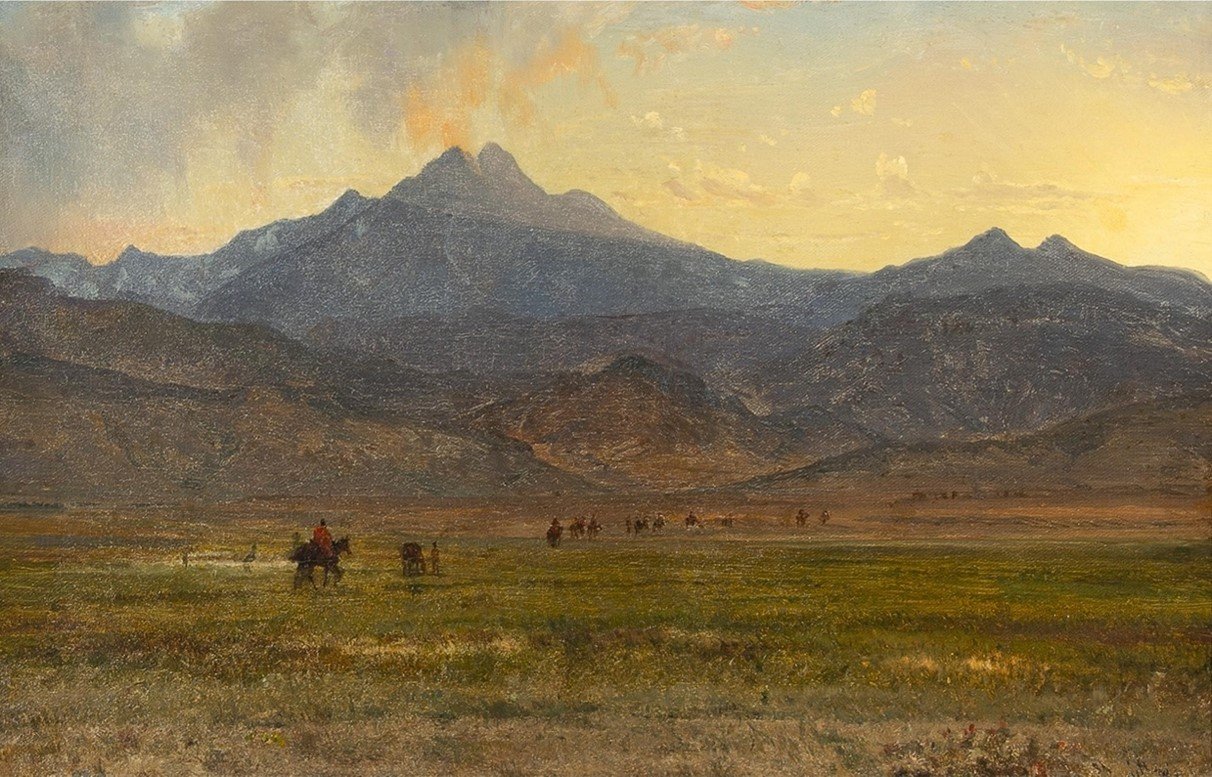

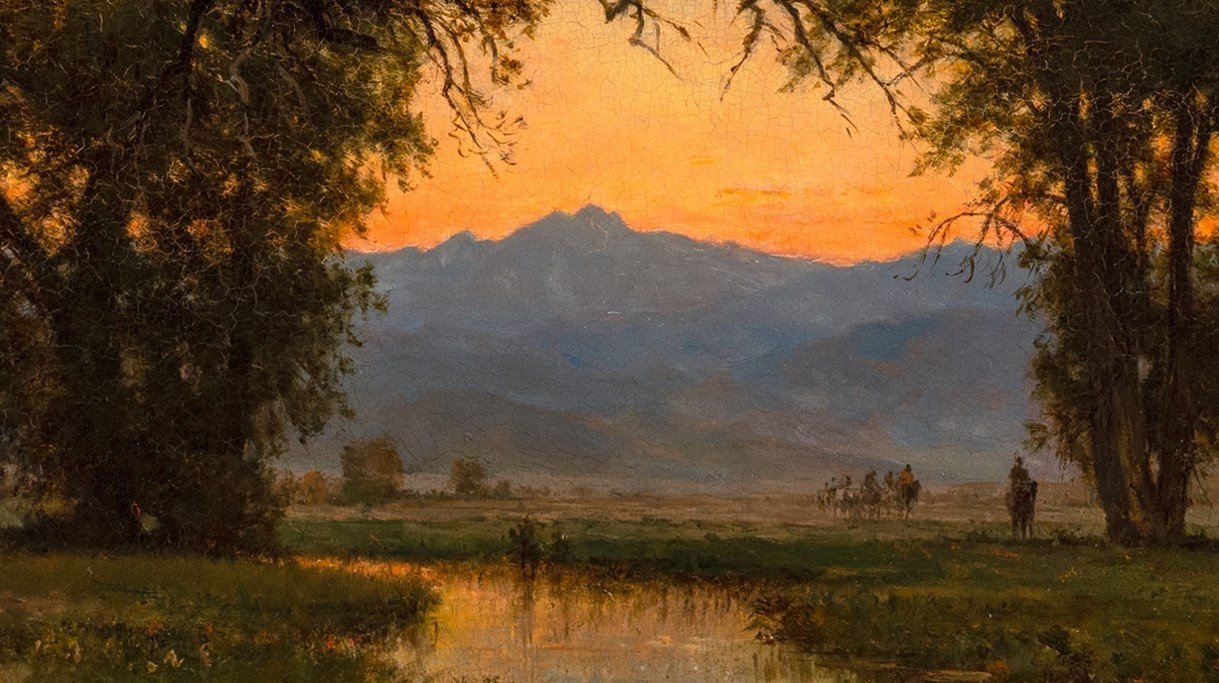

Whittredge’s largest and best-known painting of this view is On the Cache La Poudre River at the Amon Carter Museum (Fig. 2). This monumental canvas from 1876 has been called “unquestionably the masterpiece among Whittredge’s Western landscapes.”[iv] It reprises a smaller painting in the Fine Arts Museum of San Francisco with slightly disparate treatment of the foliage and the placement of the grazing deer (Fig. 3). Our painting, executed on artist’s board, is sited at the same location as these two but is markedly different in conception. Unlike them, which depict the scene in the bright light of midday with the distant snow-capped peaks dissolving into haze, it is set just before dusk, with the golden glow of the setting sun silhouetting the mountains and reflecting on the river surface. And while only deer populate the landscape in the two museum paintings, our work features a train of Native Americans on horseback returning to their encampment under the trees. There both sitting and standing figures can be seen with horses in front of two teepees, while between them another figure tends to a fire, from which smoke softly rises.

Fig. 2. Thomas Worthington Whittredge, On the Cache La Poudre River, 1876, oil on canvas, 40 ¼ x 60 ⅜ inches, Amon Carter Museum, Fort Worth.

Fig. 3. Thomas Worthington Whittredge, On the Cache La Poudre River, Colorado, 1871, oil on canvas, 15 ⅜ x 23 ⅛ inches, Fine Arts Museum of San Francisco.

Whittredge’s fascination with the West began with a journey he made during the summer of 1866. General John Pope had invited the artist to accompany him on an inspection tour of the Central Plains. The expedition embarked from Kansas and travelled the Oregon Trail as well as the South Platte River and the Cache La Poudre River in Colorado before heading south to New Mexico.[v] As Anthony Janson has noted, the expedition “had a profound effect on the artist…[and] consolidated his vision of the United States. Whittredge’s autobiography, written nearly forty years later, recalls details and events of the journey with an astonishing vividness that expresses the wonder of discovery.”[vi] Whittredge wrote of this experience:

“I had never seen the plains or anything like them. They impressed me deeply. I cared more for them than for the mountains, and very few of my Western pictures have been produced from sketches made in the mountains, but rather from those made on the plains with mountains in the distance. Often on reaching an elevation, we had a remarkable view of the great plains. I had never seen any effect like it…Nothing could be more like an Arcadian landscape than was here presented to our view.”[vii]

Our painting is just such a view—“made on the plains with the mountains in the distance”—and one of Whittredge’s most accomplished compositions. The artist’s focus on this shaded grove of towering trees is somewhat of a departure from his other Western landscapes, which tend to show the vast expanse of the open plains in the midday and late afternoon sun. By contrast, here the trees fill the pictorial space at the outer and upper edges of the composition, framing the view of the distant peaks and emphasizing the protective nature of the canopy as a place of respite for both wildlife and people.

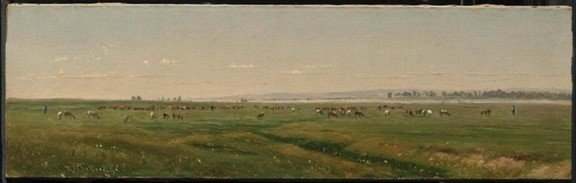

Following his westward journey in 1866, Whittredge returned twice to Colorado in the company of fellow artists, first in 1870 and again in 1871. The extant body of work from these excursions provides insight both into Whittredge’s artistic practices and to the development of his mature style during these years. While he had produced several studies from nature during his earlier period in Europe, Whittredge almost never worked in oils outdoors in the United States except in the West. In 1866, he produced several studies on half-sheets of paper—the horizontal format well-suited to capturing the plains—and two small canvases (Fig. 4).[viii] He later revisited and reworked many of these sketches into larger compositions in his New York studio.

Fig. 4. Thomas Worthington Whittredge, On the Platte River, 1866, oil on canvas, 6 ⅛ x 20 ⅛ inches, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Whittredge’s first major Western painting following his return to New York was Crossing the Ford in the collection of The Century Association (Fig. 5). In a process analogous to that seen in our painting, this large-scale canvas repeats the view of several smaller works depicted at different times and in varying light: Indians Crossing the Platte of 1867, seen at twilight;[ix] Indians Returning to Camp, Platte River, set during the day (Fig. 6);[x] and the mid-sized Indian Encampment on the Platte River of 1868 (Fig. 7), the closest in scale to our painting. [xi] Interestingly, Crossing the Ford displays two dates: 1868 and 1870. Whittredge had first exhibited the painting in 1868 under the title The Plains at the Base of the Rocky Mountains but seems not to have been satisfied with the result, as he retained the work in his studio. He returned to Colorado during the summer of 1870 specifically to revise and improve the picture.[xii] Whittredge writes in his autobiography:

“I went twice to the Rocky Mountains after my first visit, these last times by railroad. The first of these later visits was undertaken because I had gotten into some trouble with one of my pictures. On my first visit to Denver I had made a sketch from near our camping ground, from which I had begun a large picture. The trees did not suit me. I remembered a group of trees I had seen on the Cache la Poudre River, fifty miles from Denver, which I thought would suit my picture better. I undertook the journey to make sketches of them. They were finally introduced into the picture, much to its improvement.”[xiii]

Fig. 5. Thomas Worthington Whittredge, Crossing the Ford, 1868 and 1870, oil on canvas, 40 x 68 inches, The Century Association, New York.

Fig. 6. Thomas Worthington Whittredge, Indians Returning to Camp, Platte River, ca. 1866-1867, oil on canvas, 9 ½ x 13 inches, Private collection.

Fig. 7. Thomas Worthington Whittredge, Indian Encampment on the Platte River, ca. 1868, oil on canvas, 22 ¾ x 33 ½ inches, Private collection.

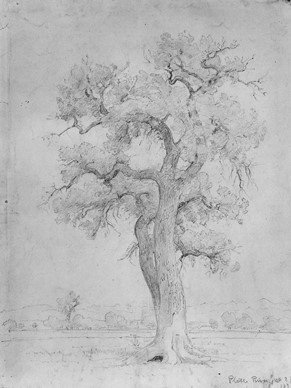

As Janson has noted, the repainting of Crossing of the Ford is confined almost entirely to the major group of trees, which are statelier than the slim trees in the earlier canvases. [xiv] Whittredge was clearly captivated by the colossal, curving, and forked cottonwood trees that he encountered in Colorado. In fact, the only certain artistic record of his return visit in 1871 is a drawing in graphite of a sprawling tree that he encountered along the Platte River (Fig. 8). The revised trees in Crossing the Ford bear a striking resemblance to those in our painting, and it seems likely that Whittredge developed the composition based on studies of the site that he mentions in his autobiography, given that the version in the Fine Arts Museum of San Francisco is inscribed on the verso “On the Cache La Poudre River/ Colorado.”

Fig. 8. Thomas Worthington Whittredge, Study of a Tree, Colorado, 1871, graphite pencil on paper, 15 x 11 ⅝ inches, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

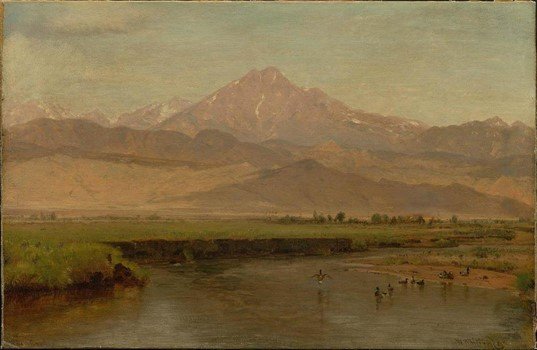

Our Indian Encampment Under Trees appears to be the earliest version of this composition and is datable to 1870 in the period during or shortly after Whittredge’s second visit to the Cache La Poudre River. The work is somewhat unusual in the artist’s production in that it is painted on artist’s board. While this light-weight support might indicate that the painting could have been executed en plein air, the finish and high degree of detail rather suggest that it may have been refined and completed in the artist’s studio. Whittredge made several studies in oil during his Colorado travels of 1870. Those works reveal a notable shift in style, displaying more atmospheric effects, partially attributable to the influence of and artistic exchange with his travel companions John Frederick Kensett and Sanford Robinson Gifford.[xv] In fact the distant view of the Rocky Mountains in our painting directly relates to Whittredge’s on-site studies from this period of Longs Peak, the highest summit in what is today Rocky Mountain National Park, located slightly over fifty miles due west of Greeley (Figs. 9-11).[xvi] Our painting appears to predate the On the Cache La Poudre River, Colorado in the Fine Arts Museum of San Francisco, which has generally been dated to 1871 based on a report in the Greeley Tribune of 19 July 1871:

“Whittredge, a New York artist of no little celebrity…has been stopping several weeks in our town, making sketches of mountain and river scenery…A large cottonwood has been sketched and partly painting, and it now looks as though it would become a remarkably fine picture…Some of his views of the Cache la Poudre are charming, for there can be no more picturesque stream in the world; these, however, have been painted this summer, and are not wholly complete.”[xvii]

However, there is no way to know which specific painting or paintings might be referred to in this passage given that the artist painted several views of the River in the early 1870s and that he visited Greeley on each of his three tours of the West.[xviii]

Fig. 9. Thomas Worthington Whittredge, Longs Peak, Colorado, 1870, oil on canvas, 14 ¼ x 22 inches, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Fig. 10. Thomas Worthington Whittredge, Longs Peak Sunset, 1870, oil on canvas, 13 ⅞ x 21 ½ inches, Private collection.

Fig. 11. Detail of the present work.

Dr. Anthony Janson has confirmed Whittredge’s authorship of our painting (written communication, 9 December 2020) and has dated our painting to 1870 on the basis of the style and the signature. Rather than a reduction of the wider composition with the additional tree at right—as in the two other versions—this painting appears to represent the artist’s first ideas for the composition. In the later paintings the trees become the subject of the work—they have become overgrown, even encroaching on the top edge of the pictorial frame in the Amon Carter canvas, and the view onto the mountains beyond has been reduced and deemphasized. By contrast, here the artist expertly uses the trees as the framework and anchor for the composition, creating windows onto areas of interest above, beyond, and below the leaves.

An early dating for our painting is also consonant with Janson’s interpretation of the symbolic content of Whittredge’s Western paintings of the late 1860s. Shortly after his election to The Century Association in 1862, Whittredge befriended the poet and fellow Centurion William Cullen Bryant, whose romantic verse considerably influenced Whittredge’s paintings. Their connection was not lost on their contemporaries: an 1879 article on the artist begins “What Bryant was to the poetry of the woodlands and brooksides, Whittredge is to their artistic and picturesque beauty.”[ixx] Janson connected the artist’s depiction of American Indians returning to their encampments at sunset—particularly the Indians Crossing the Platte of 1867—with two of Bryant’s poems.[xx] In “A Walk at Sunset,” Bryant equates the dwindling light of the evening with the vanishing of the indigenous population. He writes:

“So, with the glories of the dying day,

Its thousand trembling lights and changing hues,

The memory of the brave who passed away

Tenderly mingled. […]

The warrior generations came and past,

And glory was laid up for many an age to last.

Now they are gone — gone as thy setting blaze

Goes down the west, while night is pressing on.”

Janson further suggested that Whittredge’s paintings allude as well to the plight of the American Indians described in Bryant’s “The Prairies,” which warns America of the impermanence of civilization and the perils of progress at the expense of nature:

“The Prairies. I behold them for the first,

And my heart swells, while the dilated sight

Takes in the encircling vastness […]

Man hath no power in all this glorious work:

The hand that built the firmament hath heaved

And smoothed these verdant swells, and sown their slopes […]

Thus change the forms of being. Thus arise

Races of living things, glorious in strength,

And perish, as the quickening breath of God

Fills them, or is withdrawn. The red man, too,

Has left the blooming wilds he ranged so long,

And, nearer to the Rocky Mountains, sought

A wilder hunting-ground.”

Much like Bryant’s verses, Whittredge’s depictions of indigenous people on the plains sympathize with the dwindling of their population and the disappearance of their way of life. Although the artist expressed his fear of encountering hostile American Indians on the plains in his autobiography, he also was clearly sensitive to their plight and sought to capture their nobility. The Indians Crossing the Platte of 1867 was until now thought to be the last of Whittredge’s Western landscapes at twilight. However, it is clear that the sentiments expressed in Bryant’s poetry remained with him into the early 1870s and continued to play a role in the images of the West that he captured and created.

The part of the country that Whittredge depicted was one undergoing major upheaval during the years of his visits. Since the beginning of the nineteenth century this area of north-eastern Colorado had been populated by the Arapaho and Cheyenne, who had been driven westward from the Midwest by the Lakota. These two tribes were allied and traded peacefully with white residents. But with the arrival of new settlers following the Colorado Gold Rush of 1858–1859, the Homestead Act of 1862, and the Pacific Railway Act the same year (creating the Trans-Continental Railway), conflicts between the new immigrants and the native population increased, culminating with the Sand Creek Massacre of 1864 in which US volunteer cavalrymen slaughtered 200 Arapaho and Cheyenne people. A war between the Plains Indian groups and the United States Government followed, one which did not end until the signing of the Medicine Lodge Treaty of 1867. That Treaty provided for the removal of the Arapaho and Cheyenne from Colorado to reservations in present-day Oklahoma. However, those lands were deemed unacceptable and an alternative site was granted in 1869. Still the nomadic Plains Indians resisted resettlement, and it was not until 1874, following the Red River War and the destruction of the buffalo herds that provided the tribes’ livelihood, that they occupied the reservation, now the home of the Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribal Nation.

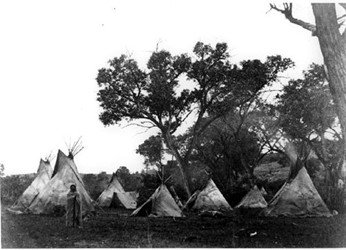

It is against these fraught political and racial conflicts that Whittredge’s painting achieves greater poignancy. The artist must have been well-aware that the Indian encampment he painted and the way of life it memorialized were soon to pass away. Even as Whittredge recorded the group of teepees with rigorous accuracy—compare his treatment with both a contemporary photograph of an Arapaho camp and a page from the artist’s sketchbook (Figs. 12-14)[xxi]—the somewhat melancholic scene of riders emerging from the haze served as a romantic and ultimately nostalgic testimony of a people’s soon-to-be vanished lifestyle, one underscored by the setting of the sun over the mountains.That Whittredge’s two later treatments of the same scene included neither the encampment nor any Native Americans may have been less an artistic choice than a factual record of a changed world now devoid of its inhabitants.

Fig. 12. Detail of the encampment in the present work.

Fig. 13. Photograph of an Arapaho Camp, 1868.

Fig. 14. Worthington Whittredge, Sketch of a teepee and Native Americans.

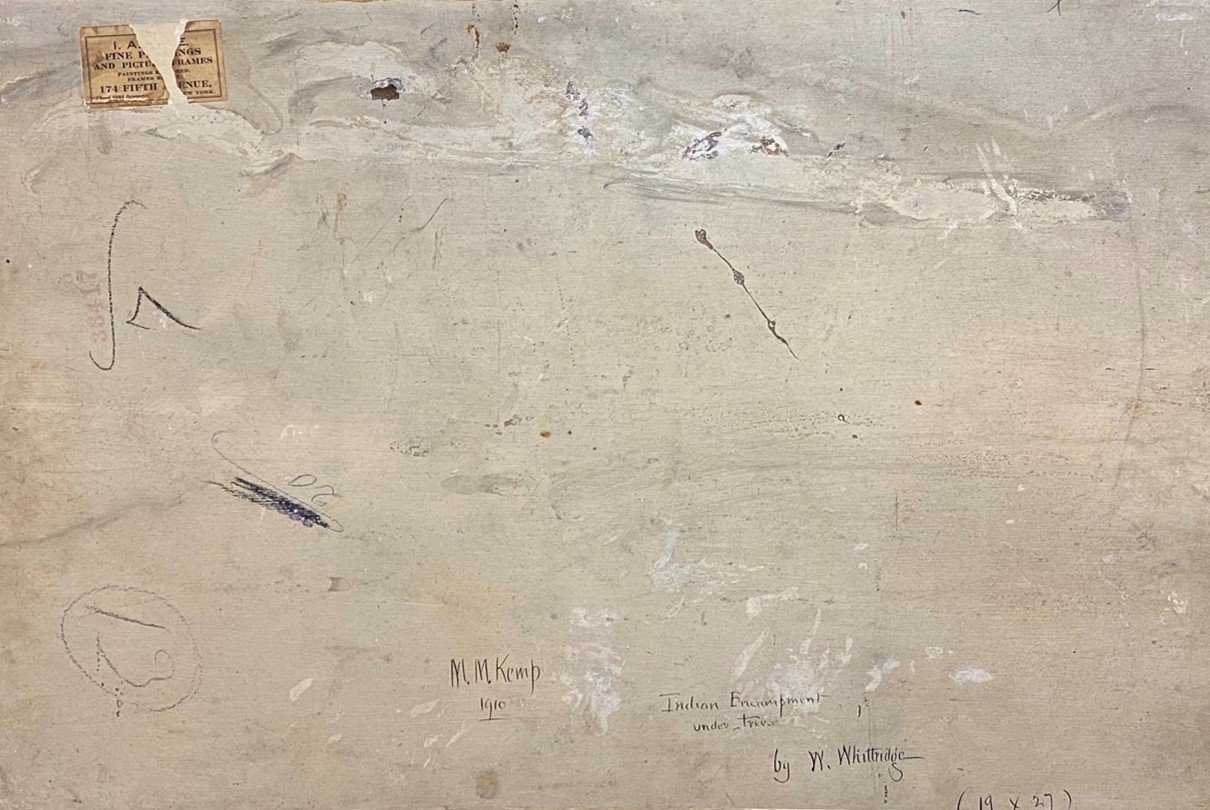

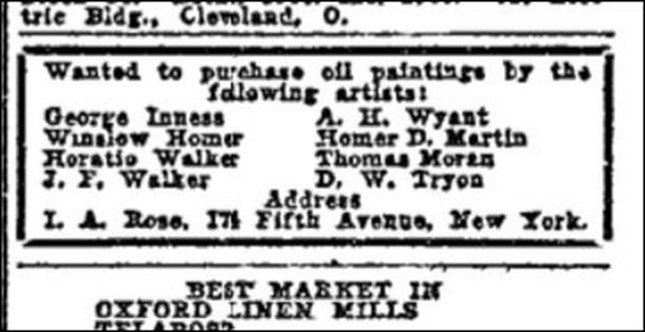

Provenance Note

The provenance of our painting is imperfectly known but can be plausibly reconstructed based on physical evidence on the verso (Fig. 15). A partial label from the New York dealer, framer, and restorer I. A. Rose, who was active in the first decade of the 20th century, is located in the upper left.[xxii] It is unclear if he was involved in the painting’s sale, but advertisements from the period show that he was active in the trade of American paintings, and was clearly seeking works by specific artists (Fig. 16).[xxiii] The verso of the painting is also inscribed “M. M. Kemp/ 1910” in the lower center, and titled to the right “Indian Encampment/ under Trees/ by W. Whittridge/ (19 x 27).” These inscriptions are written in the same hand but do not appear to be by the artist or his daughter. The spelling of the artist’s name as “Whittridge” is to be noted, but is not without precedent. The artist was said to have been born as “Thomas Worthington Whitridge” and had signed his oils “T. W Whitredge” or “T. W. Whitridge” prior to 1855. His 1849 sketchbook of a trip down the Rhine—now in the Archives of American Art—is in fact inscribed in his own hand “T. W. Whitridge”.[xxiv] He is as well cited as “Worthington Whittridge” in several publication during his lifetime.”[xxv]

Fig. 15. The reverse of the present painting.

Fig. 16. I. A. Rose Advertisement in the Philadelphia Inquirer, 5 May 1912, p. 19.

M. M. Kemp is most likely identifiable as Marion Morgan Kemp (1860–1963), and the inscription may record her purchase of the painting in 1910, or the year in which it may have been framed or conserved by I. A. Rose. Marion was the daughter of George Kemp (1826–1893), a prominent businessman and arts patron in New York City in the late 19th century. The mansion he constructed at 720 Fifth Avenue was decorated by Louis C. Tiffany, and photographs of the interior reveal that he was an avid collector.[xxvi] While no inventory or other records of his collection have been traced, Kemp was clearly associated with Whittredge and his milieu. Jervis McEntee, a fellow leading member of the Hudson River School, recorded in his diary that on 22 April 1875 he attended a meeting of artists in Whittredge’s home and that later that evening he: “called…on Mr. Tryon [George Kemp’s brother-in-law] at Mr. Kemp’s in 5th Avenue, to see a picture [George H.] Yewell painted for Mr. Kemp of the Senate Chamber in the Ducal Palace.”[xxvii] It is conceivable that George Kemp may have purchased our painting from Whittredge and that it descended to Marion, or that she later purchased it herself.

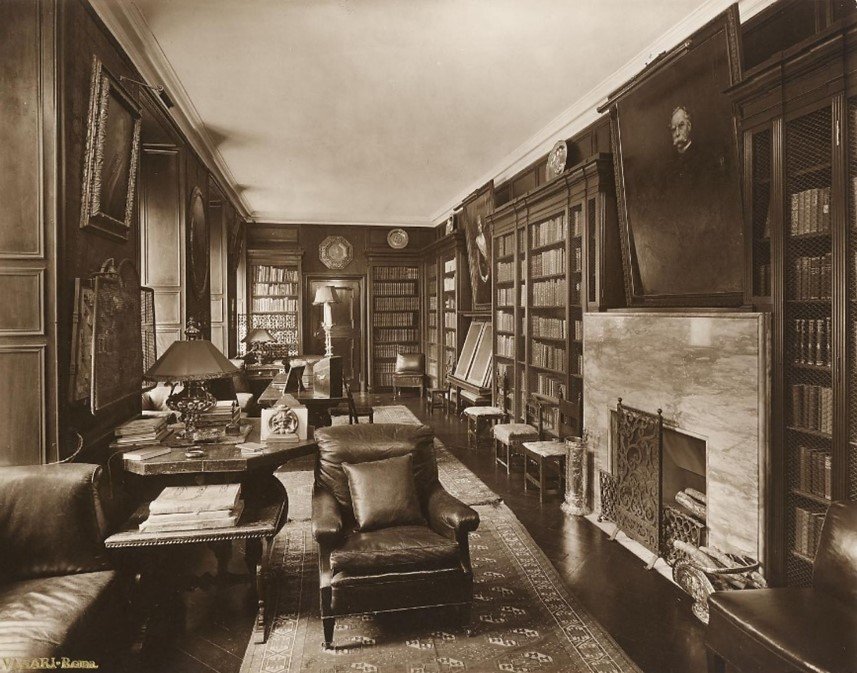

While little is known of Marion’s life, what is clear is that she moved to Rome in 1903, first renting and later purchasing in 1906 the Villa Stroganoff at 22 Via Gregoriana—the former residence of the Russian count Grigory Sergeievich Stroganoff, who assembled one of the greatest collections of antiquities and Italian paintings of the 19th century.[xxviii] Marion’s residence became a meeting place for the Roman aristocracy and was frequently visited by European royals. As the surviving photographs suggest, she decorated the 60-room villa with paintings and other opulent furnishings (Figs. 16-17).[xxix] Interestingly, in her library Marion hung portraits of her parents, George and Juliet, which she likely inherited from them and took with her to Rome. Marion never married and had no direct heirs.[xxx] Works of art and other furnishing from her villa, totaling over 1000 thousand lots, were sold at auction in Rome in 1968.[xxxi] However, the Whittredge was not among them.

How or when the Marion Kemp might have sold the Whittredge painting is not known.[xxxii] Nor how it ended up in the German collection from which it recently appeared. An intriguing possibility is suggested by the fact that Kemp lived directly across the Via Gregoriana from the Palazzo Zuccari, the home of Henriette Hertz and the eventual seat of the German art historical institute.[xxxiii] Given the proximity and importance of the institute, it is likely that Kemp had contact with Hertz, as well as with art historians or collectors through the institute. Perhaps one of these could have purchased or received the painting from the expatriate American and then returned with it to Germany. After her death Marion Kemp’s villa was in fact purchased by the Max Planck Institute, and it is now the seat of the photographic library of the Biblioteca Hertziana.

Fig. 17. Photograph of the interior of Marion Morgan Kemp’s residence in Rome.

Fig. 18. Photograph of the library in Marion Kemp’s residence, with portraits of her mother and father hanging at right.

[i] Crossing the Platte River, 40 x 60 ½ inches, The White House, Washington, D.C; Crossing the Ford, 40 x 68 inches, The Century Association, New York; On the Cache La Poudre River, 40 ¼ x 60 ⅜ inches, Amon Carter Museum of Western Art, Fort Worth; and On the Plains, 30 x 50 inches, St. Johnsbury Atheneum, St Johnsbury, VT.

[ii] Photograph of August 2017 by Jayme Perrine, taken near the Ash Avenue crossing of the Cache La Poudre River, in Greeley, CO. See: https://goo.gl/maps/oYuLAStm6chs7Sc57.

[iii] On Whittredge’s prominence and artistic achievements in this period, see: Anthony F. Janson, “Worthington Whittredge and the Crisis of Hudson River Painting,” Source: Notes in the History of Art, vol. 8, no. 1 (Fall 1988), p. 28.

[iv] Anthony F. Janson, Worthington Whittredge, Cambridge, 1989, p. 129.

[v] Anthony F. Janson, “The Western Landscapes of Worthington Whittredge,” American Art Review, vol. 3, no. 6 (November-December 1976), p. 58.

[vi] Janson, “The Western Landscapes,” p. 59.

[vii] Worthington Whittredge, The Autobiography of Worthington Whittredge, ed. John Baur, New York, 1969, pp. 45-46.

[viii] Janson, “The Western Landscapes,” pp. 60, 68, footnote 5.

[ix] The Indians Crossing the Platte of 1867 measures 11 x 22 inches and is in a private collection. See: Janson, “The Western Landscapes,” pp. 59, 64-66, illustrated. A sketch of this view at twilight measuring was also offered at Sotheby’s, New York, 25 May 1995, lot 180.

[x] Offered at Christie’s, New York, 4 December 2008, lot 159.

[xi] Sold, Sotheby’s, New York, 20 May 1998, lot 48, for $937,500.

[xii] Janson, “The Western Landscapes,” p. 66.

[xiii] Whittredge, The Autobiography of Worthington Whittredge, p. 64.

[xiv] Janson, “The Western Landscapes,” p. 66; and Janson, Worthington Whittredge, p. 120.

[xv] Janson, “The Western Landscapes,” p. 66; and Janson, Worthington Whittredge, pp. 119-125.

[xvi] Janson, Worthington Whittredge, pp. 121, 124, 125, 127, figs. 88 and 93.

[xvii] Janson, Worthington Whittredge, p. 129. The inscription was added by the artist’s daughter Olive Whittredge on information provided late in life by her father. The date added to the inscription is, however, generally considered unreliable as the artist often misdated his own work. A date of 1871 is now generally accepted. See: Marc Simpson, Sally Mills, and Jennifer Saville, The American Canvas: Paintings from the Collection of The Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, New York, 1989, pp. 96-97, 236, footnote 4; Annette Blaugrund, The Tenth Street Studio Building: Artist-Entrepreneurs from the Hudson River School to the American Impressionists, exh. cat., Parrish Art Museum, Southampton, New York, 1997, pp. 89, 91, 139, fig. 49; and https://art.famsf.org/worthington-whittredge/cache-la-poudre-river-colorado-198639.

[xviii] Although it is inscribed “Platte River,” the drawing in the Museum of Fine Arts Boston (Fig. 7) is possibly identifiable with the sketch of a large cottonwood tree mentioned in this article.

[ixx] “Worthington Whittredge,” in The Aldine, Vol 9, no. 12 (1879), p. 372.

[xx] Janson, “The Western Landscapes,” pp. 60-61.

[xxi] For the photograph see: https://www.legendsofamerica.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/Arapaho

Camp-1868.jpg. Whittredge’s sketch appears on f 38 of a sketchbook covering the years 1869–1891 in the Archives for American Art, see: https://www.aaa.si.edu/collections/worthington-whittredge-papers-9364.

[xxii] “I. A. [ROS]E / FINE P[AINTI]NGS / AND PICTU[RE] FRAMES / PAINTINGS RE[ST]ORED, / FRAMES REGILT. / 174 FIFTH AVENUE, / Phone 6694 Gramercy. NEW YORK.”

[xxiii] There are no surviving archival records or catalogues for I. A. Rose. He placed several advertisements in the Philadelphia Inquirer and the New Orleans Times-Picayune in 1912 indicating his desire to purchase American paintings, though Whittredge was not specifically named.

[xxiv] Kenneth W. Maddox, “Worthington Whittredge,” Thyssen-Bornemisza Museo Nacional website: https://www.museothyssen.org/en/collection/artists/whittredge-worthington. Cf. his painting of 1852 The Character of the Harz Mountains (Cincinnati Art Galleries; https://www.cincyart.com/solds/thomas-worthington-whittredge. For Whittredge’s sketchbook see: https://www.aaa.si.edu/collections/items/detail/worthington-whittredge-sketchbook-trip-down-rhine-river-5842.

[xxv] See, for example, Francis C. Sessions, “Art and Artists in Ohio,” Magazine of Western History, IV, no. 2 , (June 1886) p. 161, Annual Report of the Trustees of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1908, No. 39 (New York 1908), p. 103.

[xxvi] For images of the interior of the Kemp mansion, see: George William Sheldon, Artistic Houses, New York, 1883; republished in Arnold Lewis, James Turner, and Steven McQuillin, The Opulent Interiors of the Gilded Age: All 203 Photographs from “Artistic Houses,” New York, 1987. In 1910, the two rental properties that George Kemp constructed adjacent to his mansion were leased to the Duveen Brothers and served as their principal gallery in New York.

[xvii] Jervis McEntee, “Jervis McEntee’s Diary, 1874-1876,” Archives of American Art Journal, vol. 31, no. 1 (1991), p. 6.

[xviii] For information on Marion Morgan Kemp and her residence in Rome, see: Johannes Röll, “Villino Stroganoff,” in 100 Jahre Bibliotheca Hertziana, Max-Planck-Institut für Kunstgeschichte: Die Geschichte des Instituts 1913-2013, ed. Sybille Ebert-Schifferer, Munich, 2013, pp. 297-307. A portion of her former residence is now part of the Bibliotheca Hertziana.

[xxix] Röll, “Villino Stroganoff,” p. 303, footnote 47. A group of 11 photographs from the studio of the photographer Vasari in Rome records the appearance of the interior of the Marion Kemp’s home during the 1920s or 1930s.

[xxx] Röll has noted that her estate passed to her sole heir Jocelyn Pierson Kennedy Taylor (1911–2006). See: Röll, “Villino Stroganoff,” p. 306.

[xxxi] Casa di Vendite S.A.L.G.A., Rome, Vendita all’asta degli oggetti d’arte e di arredamento facenti parte dell’eredità di Miss Marion Kemp nella Palazzina di Via Gregoriana, 22 – Roma, 26 February – 7 March 1968, 2 volumes.

[xxxii] The paintings listed in the 1968 auction catalogue for the most part do not appear in the earlier photographs of her residence, which suggests both that Marion was buying and selling works over the course of her life and that there were additional works in private rooms of the villa not featured in the photographs.

[xxxiii] The Palazzo Zuccari was rented by Henriette Hertz, along with her friends Ludwig and Frida Mond, as a second home in Rome in the late 1880s. Their salon quickly became a focal point of intellectual life in Rome. Hertz eventually purchased the property in 1904 and immediately began working on founding a center of art historical studies. Just before her death she donated her library and the Palazzo Zuccari as the Biblioteca Hertziana.