Attributed to MOSES WILLIAMS

(American, 1777 – 1825)

A Group of Portrait Silhouettes

Hollow-cut silhouettes on paper

1. Portrait of a Woman

4 ⅞ x 3 ⅞ inches (12.4 x 9.8 cm)

2. Portrait of a Woman

4 ¾ x 3 ¾ inches (12.1 x 9.5 cm)

3. Portrait of a Boy

4 ¾ x 3 ¾ inches (12.1 x 9.5 cm)

4. Portrait of J. Paxson

5 x 4 inches (12.7 x 10.2 cm)

5. Portrait of a Man

4 ⅞ x 3 ⅞ inches (12.4 x 9.8 cm)

Provenance:

(nos. 1-4) Susan Burrows Swan and L. Delmar Swan, Wilmington, Delaware, ca. 1970–2010; and by descent until 2023.

(no. 5) Charles T. Donohue, Chapel Hill, North Carolina; his estate, until 2023.

Literature:

(no. 1) Susan Burrows Swan, Plain & Fancy: American and their Needlework, 1700–1850, New York, 1977, 1st edition, plate 1, illustrated, frontispiece.

Humble in scale, subtly detailed, and expertly cut, the silhouettes produced by Moses Williams rank among the most intriguing 19th-century American examples of this craft. Moses was one of the earliest artists of African descent to establish a professional career in the United States. He was born into slavery, the son of an enslaved couple, Scarborough and Lucy, who entered the household of the noted painter Charles Willson Peale in Maryland around 1775, possibly as payment for a portrait commission. Peale later moved his household to Philadelphia and emancipated the couple in 1786 through the Gradual Abolition of Slavery Act, a recently enacted Pennsylvania law that he had advocated for, requiring the freeing of enslaved people over the age of 28. Moses, then only 11 years old, remained in Peale’s service and grew up in the artist’s household amongst his many children—all of whom were trained as painters.

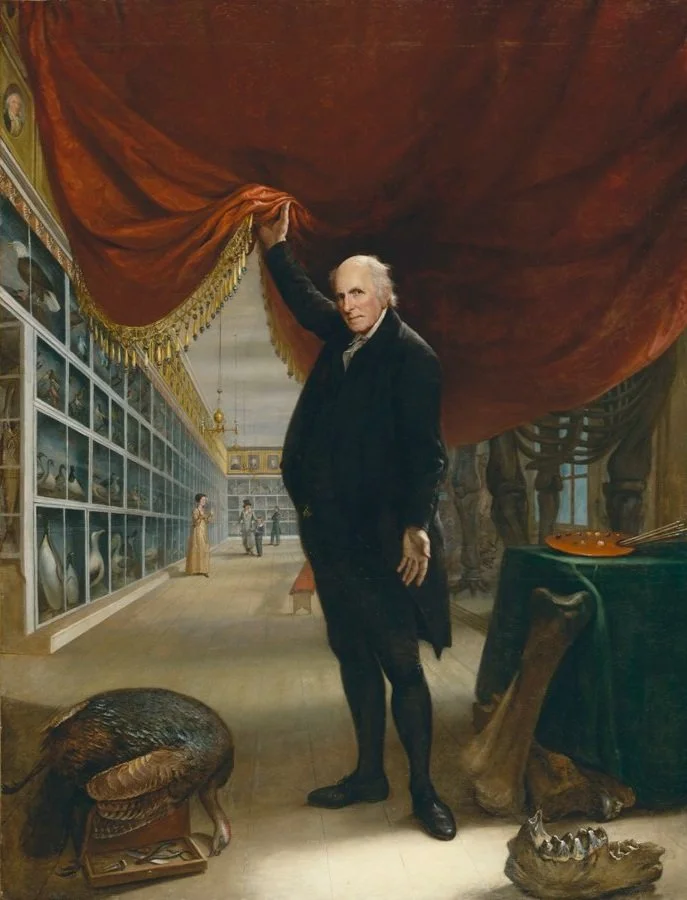

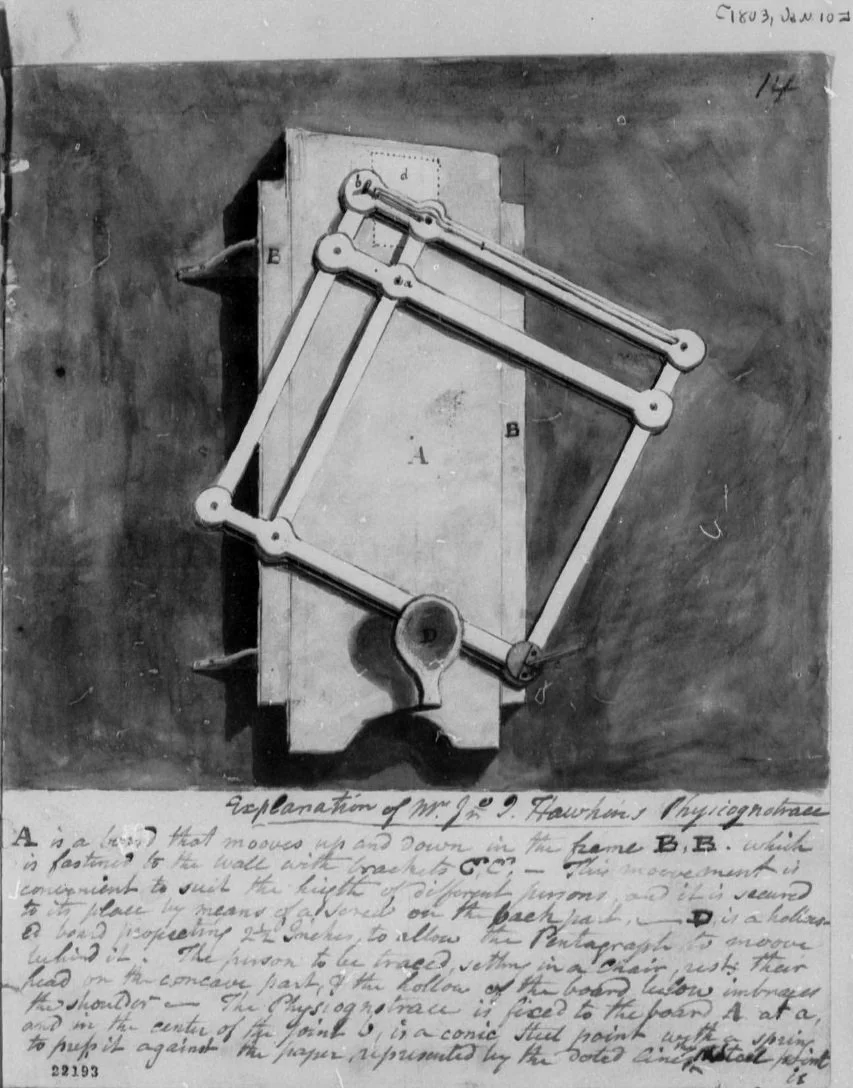

Moses Williams worked in Peale’s famous Philadelphia Museum, which consisted of a menagerie of painted portraits, natural history specimens, fossils, ethnographic artifacts, live animals, and more (Fig. 1). By 1802 Peale’s Philadelphia Museum was located in Pennsylvania’s State House, where the Declaration of Independence and the US Constitution were created. Although he was engaged in various tasks and object display, Moses’s main responsibility at the museum was operating the physiognotrace (Fig. 2)—a newly invented machine that traced a person’s profile, transferring and reducing the outline onto a small piece of paper.[i] From the impression made by the machine, Moses would hand-cut the silhouettes, creating the profiles by removing the middle of the paper and the placing the sheet against a dark background. The physiognotrace and Moses’ silhouettes quickly became among the chief attractions of the Peale Museum, as the demand for portraits and desire to capture, memorialize, and share one’s likeness increasingly became part of early American visual culture.

Fig. 1. Charles Willson Peale, Self-Portrait of the Artist in his Museum, Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Philadelphia.

Fig. 2. Illustration of the physiognotrace in a letter from Charles Willson Peale to Thomas Jefferson, Library of Congress.

In the first full year that the physiognotrace was introduced at the museum, about 80% of the visitors (roughly 8,000 people) had their profiles made by Moses Williams at a cost of eight cents each. The characteristic “MUSEUM” stamp appears on all silhouettes produced at Peale’s Philadelphia Museum, and Moses Williams’ body of work is likely entirely contained within this group. Several other hands worked at the museum in different periods, including Peale himself, but in the period in which he was active (1802 until approximately 1813), Moses was chiefly responsible for the silhouettes made at the museum.[ii] His immediate success with cutting silhouettes was such that Charles Willson Peale freed him in 1802 at the age of twenty-seven—a year earlier than required by the Gradual Abolition of Slavery Act.[iii] Peale’s son Rembrandt, later recorded the circumstances of Moses’s early freedom and newfound success:

“It is a curious fact that until the age of 27, Moses was entirely worthless: but on the invention of the Physiognotrace, he took a fancy to amuse himself in cutting out the rejected profiles made by the machine, and soon acquired such dexterity and accuracy, that the machine was confided to his custody with the privilege of retaining the fee for drawing and cutting. This soon became so profitable, that my father insisted upon giving him his freedom one-year in advance. In a few years he amassed a fund sufficient to buy a two story brick house, and actually married my father’s white cook, who during his bondage, would not permit him to eat at the same table with her.”[iv]

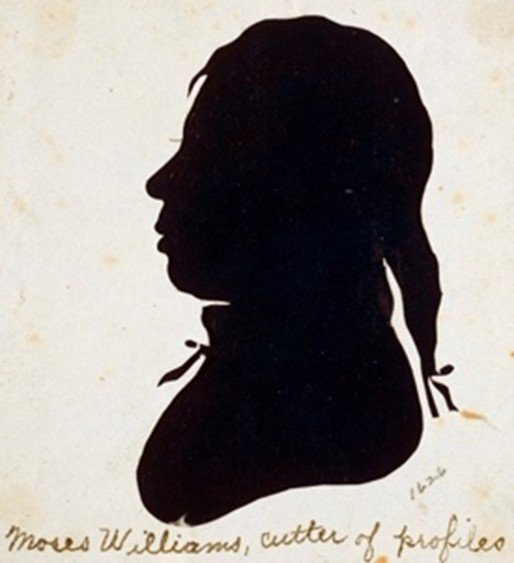

While this and other writings by Rembrandt, who was roughly a year younger than Moses and grew up alongside him in the Peale household, reveals a slight disdain for Moses, Charles Willson Peale’s brief and scattered mentions of him are always glowing and speak to the high-quality of Moses’s silhouette cutting. In one particularly intriguing case, Peale mentions encountering a southern man who asked that Peale make a silhouette of him, but he rebuffed him: “Moses has made him a good one, [but] being from Carolina he did not at first relish having it done by a Molatta, however I convinced him that Moses could do it much better than I could.”[v] Two images of Moses Williams himself are known—one a silhouette and possible self-portrait (Fig. 3) and the other a painting by Rembrandt Peale, in which Moses is thought to have served as the model (Fig. 4).[vi]

Fig. 3. Silhouette of Moses Williams (Possible Self-Portrait), Library Company of Philadelphia.

Fig. 4. Rembrandt Peale, Man in a Feathered Helmet, ca. 1805–1813, Bernice Pauahi Bishop Museum, Honolulu.

Moses Williams’ significance and the scope of his production at the Peale Museum has until recently been overlooked—a circumstance all too common for historic artists of color. And the ephemeral and personal nature of paper silhouettes has resulted in most not having survived. The group presented here, each bearing the Philadelphia Peale Museum’s characteristic “MUSEUM” blind stamp, have been attributed to Moses Williams on the basis of style and technique. Williams was especially known for his ability to capture details like the falling of a single lock of hair or the delicate fabric of a necktie, and his silhouettes often exhibit pentimenti—deviations in the cut profile from the physiognotrace’s thin embossed lines on the paper, still visible on several examples here. Almost all of the sitters in our silhouettes are unknown, except for that inscribed J. Paxon, almost certainly identifiable as the Pennsylvanian John Paxson (1773–1850).[vii] The Portrait of a Man also displays one of the characteristic paper features of Philadelphia museum silhouettes—the “AM” found in the upper right is short for “AMIES,” the mark of the Amies Dove paper mill in Lower Merion Township outside Philadelphia, which produced some of the highest-quality paper available in the day.

A significant group of silhouettes given to Moses Williams is in the collection of the Philadelphia Museum of Art. We are grateful to Dr. Anne Verplanck for her assistance in cataloguing these works.[viii]

[i] The physiognotrace was developed by the English inventor John Isaac Hawkins, who gave one of the machines to Peale for use in his museum. The physiognotrace operated by tracing around the face of the sitter with a small brass bar that was attached to a pantograph, a device for copying, which traced the profile onto a sheet of paper with a metal stylus. The physiognotrace was fastened to a wall, and a visitor would place their cheek against a concave plate for steadiness while the bar passed along their profile, recording their features. This process was described by Peale in a letter to Thomas Jefferson in January 1803, which included the drawing reproduced here. For a discussion of the physiognotrace, see: Penley Knipe, “Paper Profiles: American Portrait Silhouettes,” Journal of the American Institute for Conservation, vol. 41, no. 3 (Autumn-Winter, 2002), pp. 215-217.

[ii] In addition to those silhouettes cut by Moses Williams or Charles Willson Peale, some silhouettes were cut at the museum by visitors who wanted to save the eight-cent fee by paying only for paper at a cost of one cent. Additionally, two additional cutters active at the museum after Moses Williams’ death are known—Elizabeth Hampton in 1827 and Elizabeth Meigs in 1834. See: Gwendolyn DuBois Shaw, “‘Moses Williams, Cutter of Profiles’: Silhouettes and African American Identity in the Early Republic,” Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society, vol. 149, no. 1 (March 2005), pp. 35-36; Knipe, “Paper Profiles,” p. 215; and Carol Soltis, The Art of the Peales in the Philadelpha Museum of Art: Adaptations and Innovations, Philadelphia, 2017, pp. 126-129.

[iii] After he was emancipated Moses adopted the surname Williams, which was the same name taken by his father, Scarborough, when he was freed in 1786.

[iv] Quoted from DuBois Shaw, “Moses Williams, Cutter of Profiles,” pp. 25-26.

[v] Quoted from DuBois Shaw, “Moses Williams, Cutter of Profiles,” pp. 26-27.

[vi] For a discussion of Moses Williams’ possible self-portrait, see primarily: DuBois Shaw, “Moses Williams, Cutter of Profiles; and Gwendolyn DuBois Shaw, Portraits of a People: Picturing African Americans in the Nineteenth Century, exh. cat., Seattle, 2006.

[vii] There were several members of the Paxson family with first names beginning with J, but John seems the most likely candidate, particularly as this silhouette had been acquired by Susan Burrows Swan along with a silhouette by an unknown artist (unmarked) of Anna (Paxson) Richardson (1775–1863), John Paxson’s older sister. For the history of the family and biographical details of these figures, see: https://sites.rootsweb.com/~paxson/Paxson5Gen.html#125John.

[viii] For her writings on Peale silhouettes, see: Anne Verplanck, “The Silhouette and Quaker Identity in Early National Philadelphia,” Winterthur Portfolio, vol. 43, no. 1 (Spring 2009), pp. 41-78.